Social Cohesion Insights 08: Religion and social cohesion in Australia

Social scientists have long predicted that the influence of religion on public life would decrease with modernisation.[1] While Christianity is still a major social and political force in countries like the United States, in Australia and other liberal democracies, increasing numbers of people report being non-religious. However, as this Insights piece shows, religious beliefs continue to shape how some Australian communities see themselves, the wider world, and how they connect with others.

Starting in 2007 and administered each year since 2009, the Mapping Social Cohesion surveys are a unique source of data about how Australians view their lives and the communities they live in. The surveys use a systematic methodology with nationally representative samples that provide a strong basis for analysis of sub-groups. The Insights series take a deep dive into these rich data.

Introduction

Religious diversity can create unique opportunities for dialogue on matters of justice or peace—core aspects of many spiritual belief systems.[2] Conversely, religious difference can also be a threat to social cohesion. In extreme cases, religious values can become weaponised in the service of political ideology. Regardless, religion remains a ‘significant variable in social identity’ for many people across the world.[3]

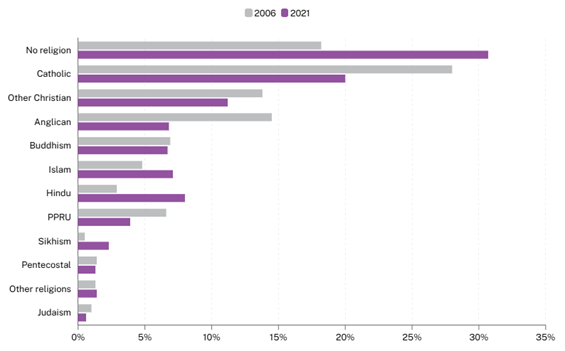

There is a great deal of variation between countries and regions on measures of religious significance. The Worlds Values Survey (WVS), which uses nationally representative samples, asks respondents to indicate how important religion is in their lives. A large proportion (42%) of Australians surveyed in 2018 said that religion was ‘not at all important’ (Figure 1). Of the nearly 100 countries taking part in the WVS, only China, Japan, and New Zealand had a higher proportion of people who said religion was not at all important. In many other countries, religion remains ‘very’ or at least ‘rather’ important.

Figure 1. How important religion is to people in life, selected countries, 2017–23

Source:

World Values Survey/European Values Study. Years: Australia 2018, Brazil 2018, Canada 2020, Germany 2018, India 2023, Italy 2018, Malaysia 2018, Sweden 2018, United Kingdom – Great Britain 2022, USA 2017.

Despite a general trend towards secularisation, some liberal democracies continue to invoke religious values and symbolism in processes of political change. In the United States, Donald Trump has leaned into Christian nationalism (‘where God is on the side of might’[4]) as part of his political ascendancy. In 2021, for example, Trump began selling a “God Bless the USA” Bible, combining the King James version of this sacred text with foundational US political documents such as the Constitution and Declaration of Independence (an edition with Trump’s autograph will cost believers US$1,000).

Trump’s campaigners must have known that a majority (62%) of Americans identify as Christians, and a similar proportion believe religion is an important factor in their lives.[5] By appealing to this base, Trump captured 81% of White evangelical voters in the 2024 Election, and won the largest share of voters who attended any religious services at least once per month (religiously unaffiliated voters were more likely to vote Democrat).[6]

Religion in Australia

In Australia, religion has usually played a ‘relatively muted role’ in public life,[7] though Prime Ministers from both major parties have sometimes expressed Christian values. Perhaps appreciating this context, future Prime Minister Scott Morrison said in his maiden speech to Parliament in 2008,

“My personal faith in Jesus Christ is not a political agenda[…] for me, faith is personal, but the implications are social.”[8]

This view is indicative of how religion in Australia may be present, though ‘muted,’ in political and social life. Following his retirement from politics, Morrison published a book lamenting how causes like climate action or gender equality were replacing ‘traditional religion’ in Australia as sources of meaning and ‘moral purpose’.[9] Faith, in this view, is part of the search for the ‘ultimate meaning of life’; it is a core aspect of believers’ sense of self and purpose in the world, and can also reflect their normative, ‘moral universe’.[10]

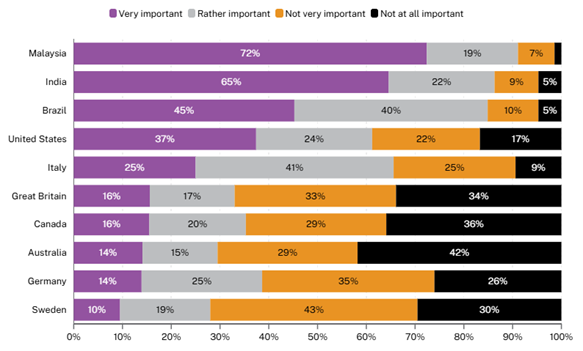

Religious affiliation has been declining in Australia. Census data on religion is coded according to the Australian Standard Classification of Religious Groups (ASCRG).[11] Analysis of responses in this way (i.e., grouping major world religions) shows a steep decline in affiliation with Christianity over the last five decades, with a concurrent increase in people who say they have ‘no religion’ and a modest but noticeable increase in other religions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Religious affiliation in Australia, 1971–2021

Source: ABS 2022

Source: ABS 2022

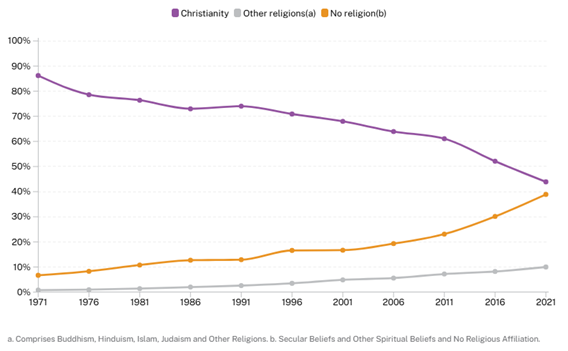

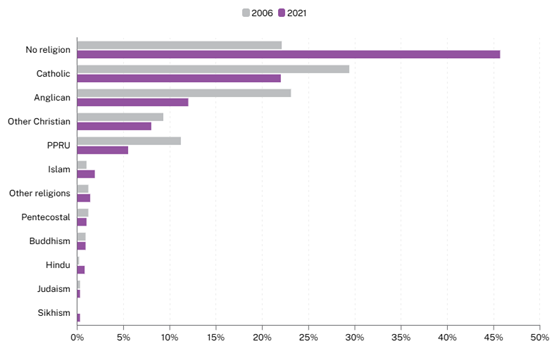

Disaggregating this data further, among the Australian-born population, the proportion saying they had ‘no religion’ more than doubled from 22% to 46% between 2006–21 (Figure 3). Every major religious group saw a decrease in representation among the Australian-born population – except Islam, which rose from 1 to 2%. The proportion of Australian-born residents who identified with Buddhism or Judaism stayed constant at less than 1%.

Figure 3. Religious affiliation as % of the population (Australian-born), 2006 and 2021

Source: ABS Census 2006 & 2021.

Note: PPRU = Other Protestant, Presbyterian and Reformed and Uniting Church. See Bouma and Halafoff, 2017.[12]

Figure 4. Religious affiliation as % of the population (overseas born), 2006 and 2021

Source: ABS Census 2006 & 2021.

Note: PPRU = Other Protestant, Presbyterian and Reformed and Uniting Church. See Bouma and Halafoff, 2017.

Among the overseas-born population, the ‘no religion’ group also increased, though more slowly, from 18% to 31% over the same period (Figure 4). There were concurrent decreases in migrants’ affiliation with Christianity or Catholicism. In contrast, Hinduism, Islam, and Sikhism each grew by 5.1, 2.3, and 1.8 percentage points, respectively. The proportion of overseas-born people who identified with Judaism declined from 1.0% to 0.6%. Taken together, these statistics indicate a small but growing proportion of Australians who identify with Islam or Eastern religions, likely reflecting the growth in the proportions of immigrants from source countries such as India, Malaysia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.[13]

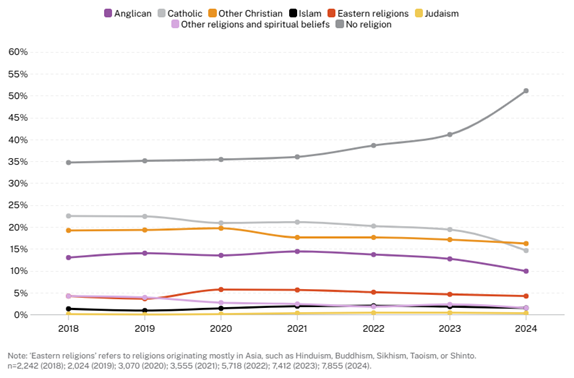

Using a representative sample of the Australian population, the 2024 Mapping Social Cohesion (MSC) survey demonstrated similar levels of religious affiliation to the Census.[14] More than half (51%) of all respondents to the 2024 MSC survey indicated that they had ‘no religion’, while 41% identified with Anglican, Catholic, or other Christian denominations. A further 8% identified with another religion or spiritual belief system. (Figure 5 breaks this down further).

Figure 5. Religious affiliation, MSC, 2018–24

Religiosity in the Mapping Social Cohesion study

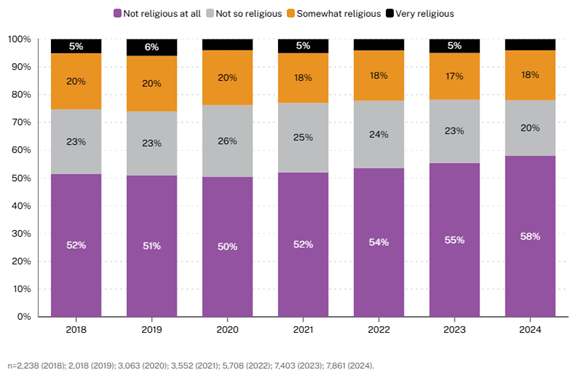

Another way of understanding the significance of religion is to examine the extent to which people consider themselves religious. By this measure, 58% of MSC respondents in 2024 said they were ‘not religious at all,’ while less than 5% said they were ‘very religious.’ These proportions have not changed dramatically in recent years of the study (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. ‘Religiousness’ (weighted %), MSC, 2018–24

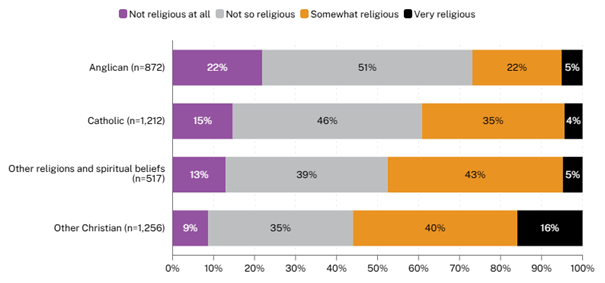

‘Religiousness’ also differs by denomination. In 2024, people who identified with a Christian denomination other than Anglican or Catholic were the most likely to be ‘very religious’ (see Figure 7). This may be explained by the ‘Other Christians’ group including Pentecostal, Apostolic, or Charismatic churches – congregations which are more likely than Catholics or Anglicans to attend services regularly. [15],[16]

Figure 7. Religiousness by denomination, MSC, 2024

Who is likely to be religious in Australia?

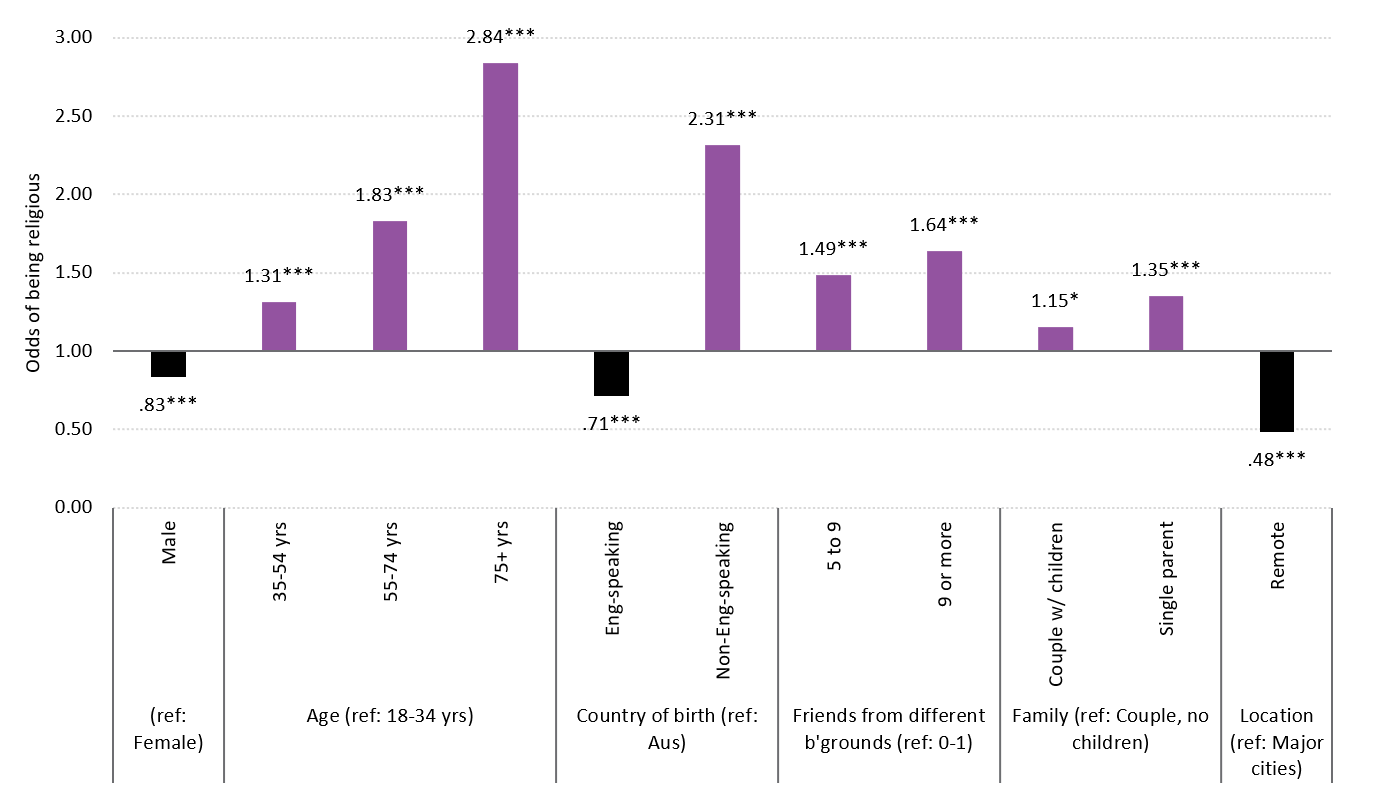

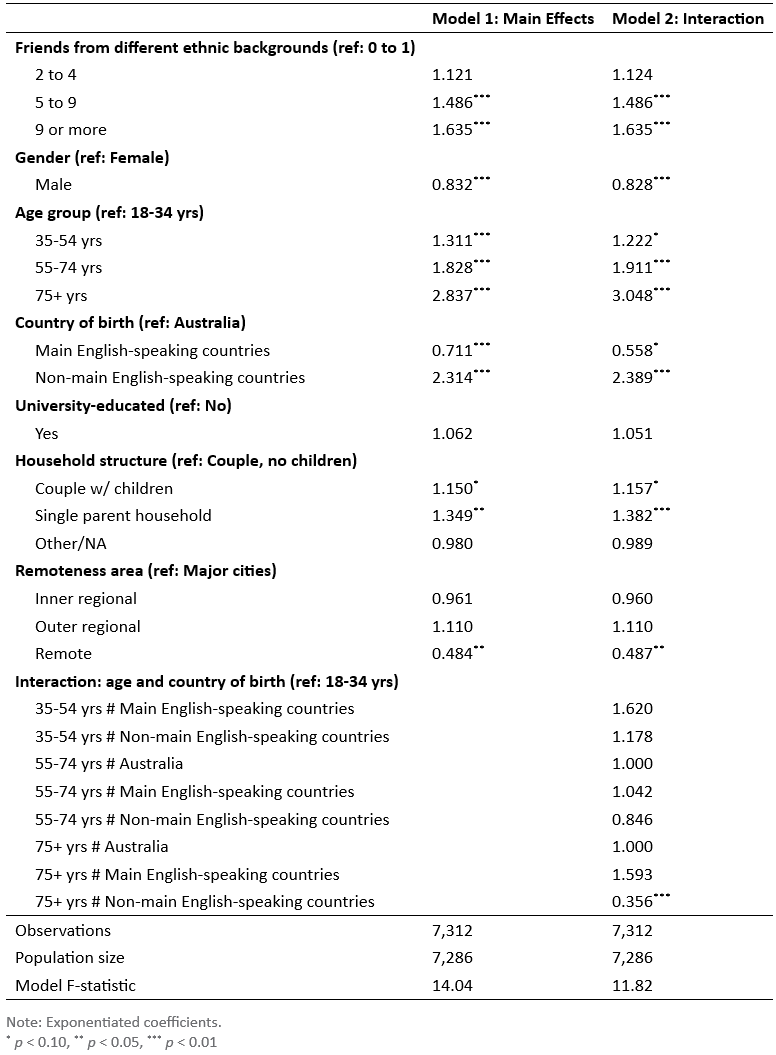

To interrogate the MSC data further, survey-weighted logistic regression models were used to identify the demographic and social factors associated with being religious. The models enable a comparison of the traits of respondents who are at least ‘somewhat religious’ to those who are not religious at all. Figure 8 plots the significant associations in terms of odds ratios (full results are provided in Appendix A). [17]

The model shows several demographic factors of interest. Men had 17% lower odds of being religious compared to women, while ‘religiousness’ increases significantly with age. Compared to 18-34-year-olds, the odd of being religious were 1.8 times higher for 55-74-year-olds and 2.8 times higher for those ages 75 and older. Participants born overseas in countries where English is the main language[18] had 29% lower odds of being religious than those born in Australia. In contrast, people born in primarily non-English speaking countries had 2.3 times higher odds of being religious than the Australian-born.

Households with dependent children (whether couples of single parents) had higher odds (15% and 35%, respectively) of being religious when compared to couples with no children. People living in remote parts of Australia had 52% lower odds of being religious compared to people in major cities (it is worth noting that inner and outer regional areas had no significant association with religiosity, when compared to cities). There was no statistically significant difference in religiosity between those with and without a university education.

People with more diverse friends (from different ethnic backgrounds to their own) had higher odds of being religious. Having 5 to 9 such friends increased the odds of being religious by 49%, and having 9 or more increased the odds by 64%.

Figure 8. Social and demographic factors associated with being religious, MSC, 2024

Note:

Note:

A ratio above 1 (purple bars) indicates higher odds of being religious, compared to the reference group (noted in brackets below each item). A ratio below 1 (black bars) indicates lower odds of being religious compared to the reference group. * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Associations here do not imply causality, and there are likely to be other factors that explain religiosity across these groups.

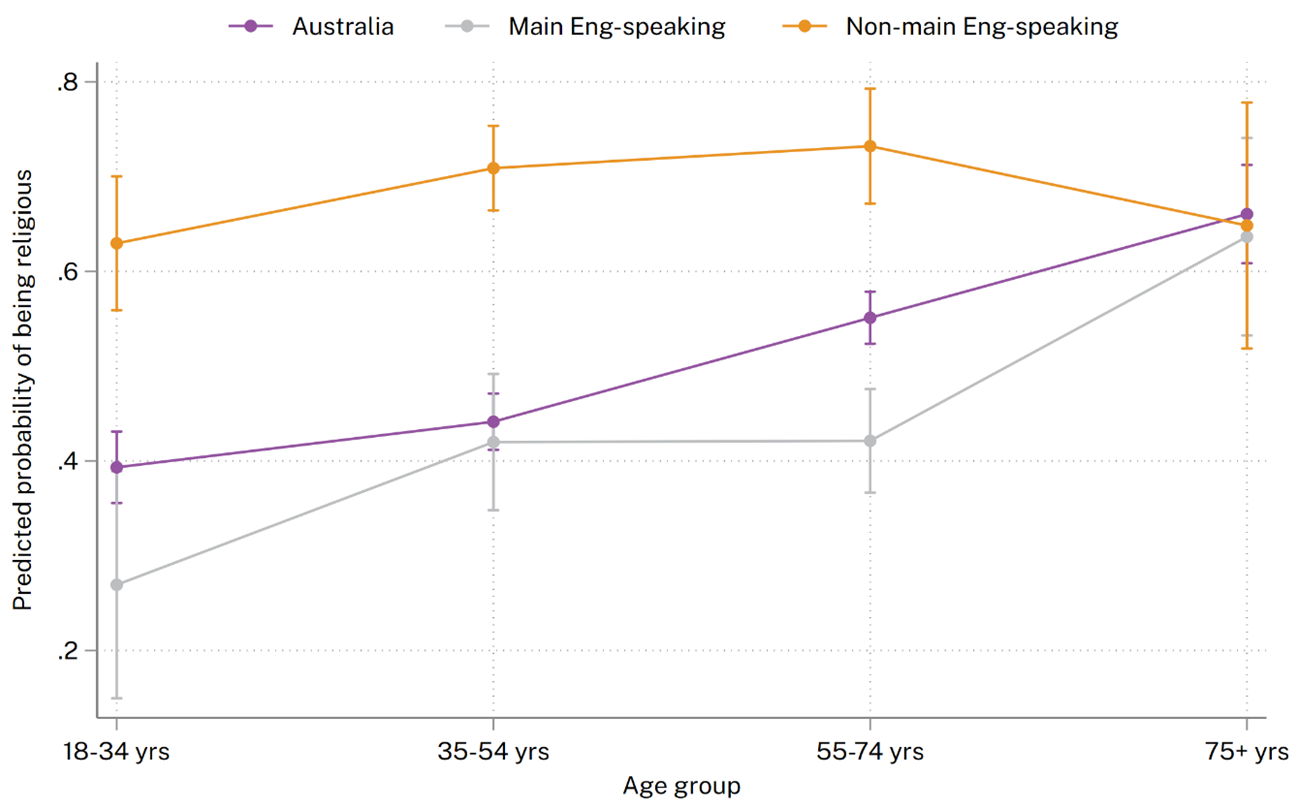

For participants born in Australia or primarily English-speaking countries,[18] the odds of being religious increase dramatically in older age groups (Figure 9). This is likely to reflect the higher prevalence of religious beliefs in earlier birth cohorts. People born in non-English speaking countries, however, were more likely to be religious in younger age groups, with religiosity less pronounced in older birth cohorts.

Figure 9. Effect of age and country of birth on religiosity, MSC, 2024

Note: n=7,312

Understanding how religion affects social cohesion

The MSC survey enables examination of how being religious (or not) is correlated with different aspects of social cohesion. The study adopts a multidimensional framing of social cohesion that includes the domains of belonging, worth, social inclusion and justice, participation, and acceptance.[19]

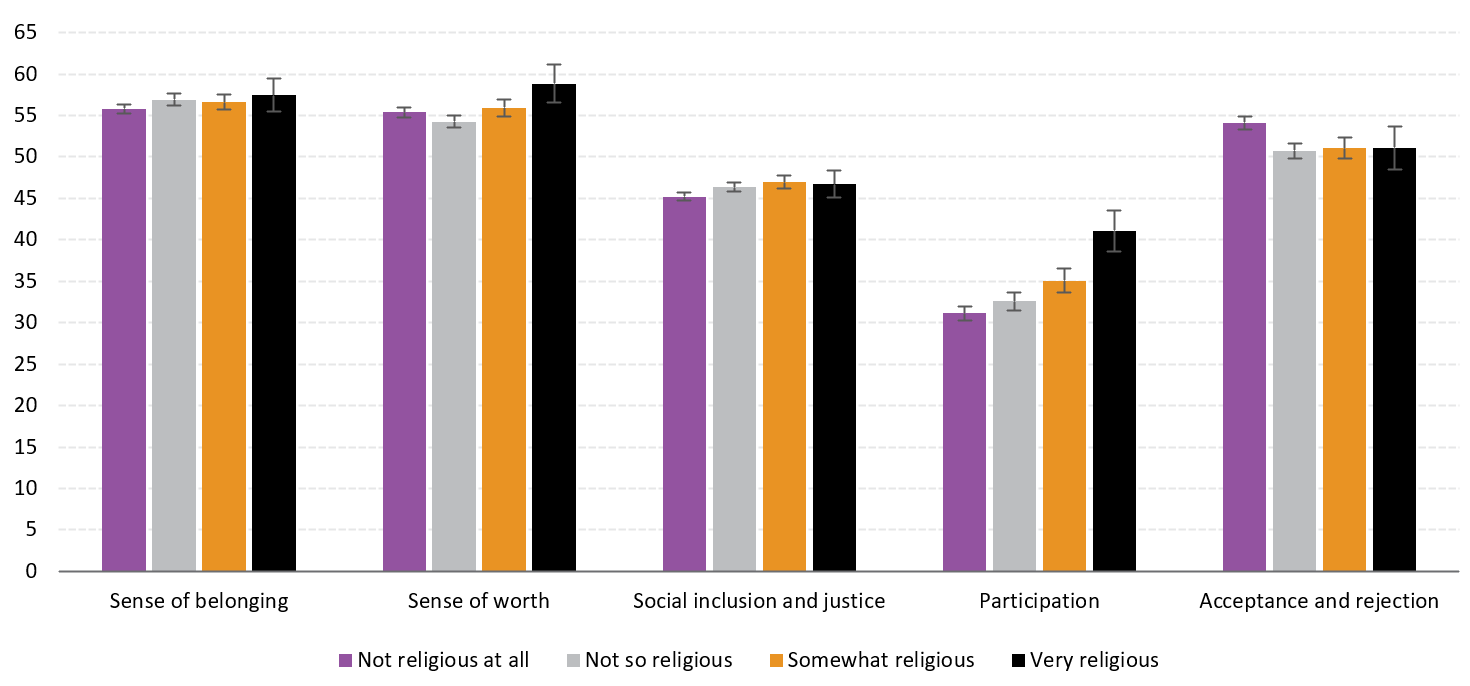

While there was minimal variation across most domains for levels of individual ‘religiousness’ in the 2024 data, there are some notable exceptions (Figure 10). The sense of worth among those who considered themselves to be ‘very religious’ was 3 – 5 points higher than those who were not religious at all, or ‘not so’ religious. In the Scanlon Index, ‘worth’ is measured by the extent to which people feel they are treated with respect, whether they feel the things they do in life are worthwhile, levels of financial security, and overall happiness.

Scholarly research indicates that participation in religious communities can foster traits like compassion and forgiveness, which in turn enhance feelings of respect and being valued by others.[20] Receiving spiritual support from fellow believers is also associated with higher self-worth and respect.[21] Believing in a loving or supportive God, frequent prayer, and strong congregational ties have also been linked to a propensity of individuals to ‘find meaning in life’.[22]

Figure 10. Mean social cohesion domain scores by ‘religiousness,’ MSC, 2024

Note: Survey weights applied (n=7,855). Error bars = 95% confidence intervals.

A more pronounced variation can be seen in the domain of participation, which is measured by political or civic activities, involvement in social groups, and unpaid volunteer work. The participation domain score for the very religious in the 2024 MSC survey was significantly higher than all other groups – 10 points higher than those who said they were not religious at all.

In other contexts, research has shown that religiousness is associated with higher rates of volunteering, charitable giving, and involvement in civic organisations. However, these forms of social participation are often channelled through religious organisations themselves, rather than organisations that usually attract a larger share of volunteers, like sports clubs.[23] Religion is also positively linked to political involvement: religious organisations often recruit members into political activities such as voter registration drives.[24]

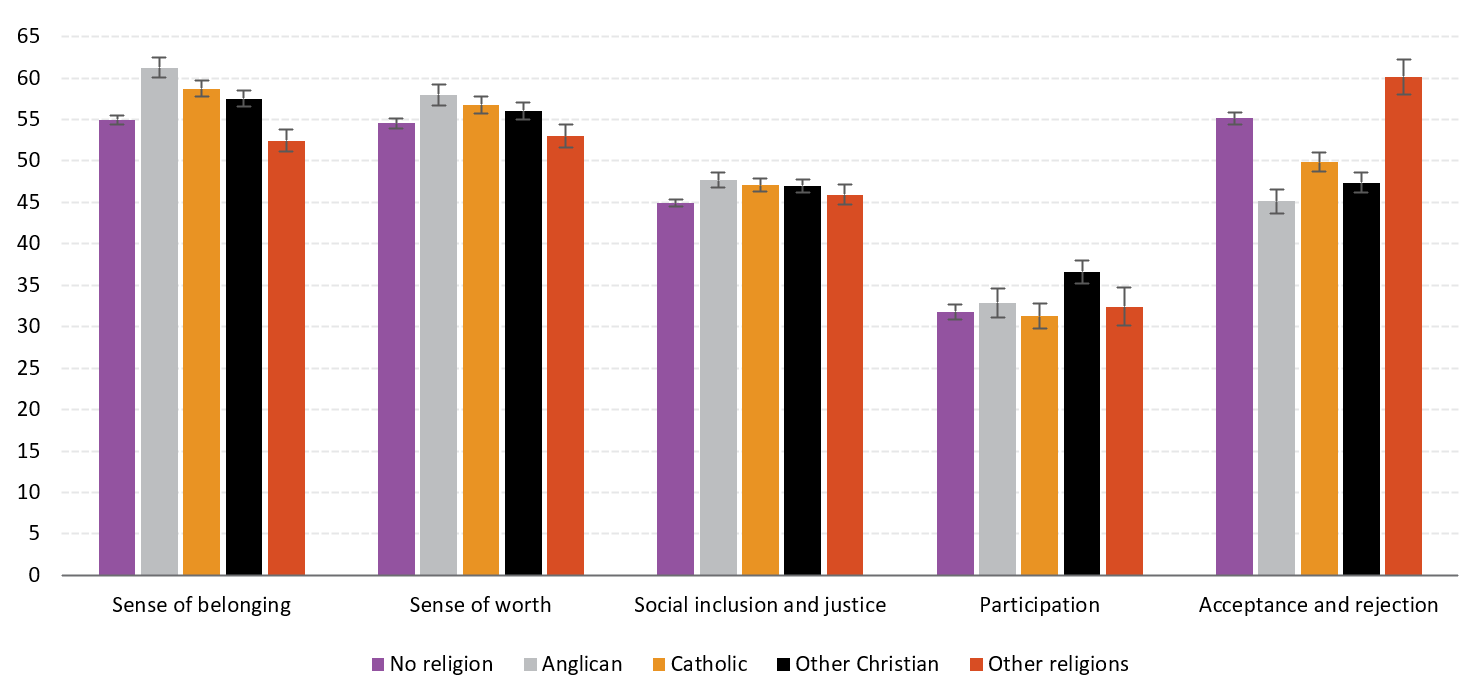

Examining the social cohesion domain scores for different religious groups in Australia reveals more variation (Figure 11). Christian denominations, for instance, had significantly higher scores on the belonging domain than other religions, or the non-religious. In the Scanlon model, this domain is measured by individuals’ perception of belonging both to the local neighbourhood and to the nation, pride in the Australian ‘way of life and culture,’ and feelings of isolation or safety. With Christianity still the largest religious institution in Australia, and the historical infusion (though ‘muted’) of Christian values with ‘Australian culture,’ this finding is perhaps not surprising. Also unsurprising is the higher levels of participation among the ‘Other Christian’ denominations; as noted, this category includes the highly active Pentecostal and Uniting Church congregations.[25]

Figure 11. Mean social cohesion domain scores by religious group, MSC, 2024

Note: Survey weights applied (n=7,855). Error bars = 95% confidence intervals.

The domain of acceptance and rejection shows the most variation among religious groups. Scores on this domain are calculated from items such as support for government assistance to ethnic minorities, and the relationship between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and the wider population. Combined, non-Christian religions (Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, etc.) show the highest levels of ‘acceptance’ when compared to other groups (15 points higher than Anglicans, for example), while non- religious participants also have higher levels of acceptance than Christians.

Acceptance also appears significantly higher among the non-religious when compared to Christian denominations. It is worth noting, however, that previous studies using MSC survey data have found more positive views among frequent churchgoers on specific issues such as cultural diversity and immigration.[26] As the domains scores comprise multiple survey items, more research is needed to unpack the specific factors that determine how ‘accepting’ people are.

Discussion

Religion in Australia has been described as a ‘quiet backdrop of themes and potentials for interaction against which power relations can affect states of social cohesion.’[27] This ‘quiet backdrop’ is now characterised by increasing religious diversity and a complex social environment of values, beliefs, and intergroup relations.

As the main source countries of immigrants to Australia have shifted from Europe to parts of Asia, the proportion of the population that identifies with non-Christian religions has increased considerably. Between 1996 – 2021, the population count of Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and Sikhs grew from around 480,000 to over 2.3 million (almost one-in-ten Australians) over this period.[28] Combined, the non-Christian religions are also now a larger proportion of the population than Anglicans – a congregation historically entwined with the establishment of Australia after colonisation.

Despite the overall decline in identification with organised religions, recent Scanlon surveys show that ‘religiousness’ has not changed substantially in recent years. On the one hand, older age appears a significant driver of being religious. People who are over the age of 55 (regardless of birthplace) are between 1.8 and 2.9 times more likely to be at least ‘somewhat’ religious, compared to the under 35 age group. This is likely mediated by the interaction between life stage and birthplace. Migrants from countries where English is not the main language (i.e., most new arrivals to Australia) are both younger and more religious than their Australian-born counterparts.

The Australian experience underscores that religion is neither disappearing completely, nor is it uniformly influential. Rather, it continues to evolve within a shifting cultural and demographic landscape. For some groups, religious practice enhances belonging and self-worth. The ‘very religious’ may also be more likely to engage in forms of social, political, and civic activism than their non-religious counterparts. However, this occurs through the prism of faith itself; religious institutions expect participation based on shared values. For other groups, particularly the non-religious or members of non-Christian traditions, higher levels of acceptance of cultural diversity and Indigenous recognition suggest alternative pathways to cohesion.

The findings highlight the importance of recognising religion’s ambivalent role: it can provide strength, solidarity, and moral purpose, but also carry the risk of exclusion or insularity. As Australia becomes more diverse, efforts to sustain social cohesion will require not only respect for freedom of belief but also intentional strategies to foster shared values across both religious and secular communities.

Appendix A

Table 1. Logistic regression models predicting religiosity, MSC 2024

Endnotes

[1] Farida Fozdar, “Christianity in Australian National Identity Construction: Some Recent Trends in the Politics of Exclusion,” in Minority Groups: Coercion, Discrimination, Exclusion, Deviance and the Quest for Equality, ed. Dan Soen, Mallory Shechory, and Sarah Ben David (New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2012).

[2] Douglas Ezzy, Gary Bouma, Greg Barton, et al., “Religious Diversity in Australia: Rethinking Social Cohesion,” Religions 11, no. 2 (2020): 2.

[3] Gary D. Bouma and Rod Ling, “Religion and Social Cohesion,” Dialogue (Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia) 27, no. 2 (2008): 41.

[4] Robyn Whitaker, “Is Trump the Antichrist? — And Other Hard Questions Christians Should Be Asking,” ABC Religion & Ethics, June 4, 2025.

[5] Pew Research Centre, “U.S. Adults,” 2023-24 U.S. Religious Landscape Study Interactive Database, 2025.

[6] Hannah Hartig, Scott Keeter, Andrew Daniller, and Ted Van Green, Behind Trump’s 2024 Victory, a More Racially and Ethnically Diverse Voter Coalition (Pew Research Center, 2025).

[7] Carolyn Evans, “Religion and the Secular State in Australia,” in Religion and the Secular State: National Reports, ed. Javier Martinez-Torron and W. Cole Durham (Madrid: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2015), 83–97.

[8] ABC Radio National, “Scott Morrison on Faith,” ABC Listen, August 29, 2018.

[9] Robyn Whitaker, “‘God Has a Plan for You’: Scott Morrison’s Faith Seems Sincere, but Ultimately It Is Just Too Small,” ABC Religion & Ethics, May 15, 2024.

[10] ALRC, Maximising the Realisation of Human Rights: Religious Educational Institutions and Anti-Discrimination Laws, Final Report no. 142 (Australian Government, Australian Law Reform Commission, 2023).

[11] ABS, “Australian Standard Classification of Religious Groups, March 2024,” Australian Bureau of Statistics, March 26, 2024.

[12] Gary D. Bouma and Anna Halafoff, “Australia’s Changing Religious Profile—Rising Nones and Pentecostals, Declining British Protestants in Superdiversity: Views from the 2016 Census,” Journal for the Academic Study of Religion 30, no. 2 (2017): 129–43.

[13] ABS, “Permanent Migrants in Australia, 2021,” Australian Bureau of Statistics, March 29, 2023.

[14] The analysis in this section uses unit record data from the Mapping Social Cohesion timeseries (2007–24). For more information about the study sample and methodology, see O’Donnell and Qing Guan, Mapping Social Cohesion, no. 2024 (Scanlon Foundation Research Institute, 2024).

[15] Bouma and Halafoff, “Australia’s Changing Religious Profile—Rising Nones and Pentecostals, Declining British Protestants in Superdiversity.”

[16] People who followed religions such as Islam also had higher levels of religiosity, but their numbers in the Scanlon surveys are too small to provide nationally representative estimates.

[17] An odds ratio greater than 1 indicates higher odds of being religious, while a value less than 1 indicates lower odds.

[18] New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, Canada, the US, and South Africa.

[19] For more information about the items included in the Scanlon Index of Social Cohesion, see O’Donnell and Guan, Mapping Social Cohesion.

[20] Neal Krause, Peter C Hill, and Gail Ironson, “Evaluating the Relationships among Religion, Social Virtues, and Meaning in Life,” Archive for the Psychology of Religion 41, no. 1 (2019): 53–70.

[21] Neal Krause, “Religious Involvement and Self-Forgiveness,” Mental Health, Religion & Culture 20, no. 2 (2017): 128–42.

[22] Ali Birinci and Şerife Ericek Maraşlıoğlu, “The Mediating Role of Attitudes Towards Psychology of Religion Course in the Relationship Between Theology Students’ Levels of Religious Attitude and Finding Meaning in Life,” Rize İlahiyat Dergisi, no. 28 (April 2025): 28.

[23] Susanne Wallman Lundåsen, “Religious Participation and Civic Engagement in a Secular Context: Evidence from Sweden on the Correlates of Attending Religious Services,” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 33, no. 3 (2022): 627–40.

[25] See also Miriam Pepper, Ruth Powell, and Gary D. Bouma, “Social Cohesion in Australia: Comparing Church and Community,” Religions 10, no. 11 (2019): 11.

[26] Pepper et al., “Social Cohesion in Australia,” 11.

[27] Bouma and Ling, “Religion and Social Cohesion,” 47.

[28] ABS, “Religious Affiliation in Australia,” Australian Bureau of Statistics, July 4, 2022.