Social Cohesion Insights 09: Stretched thin: the emotional toll of financial stress

What are the personal and emotional costs of living under financial stress? Continuing cost-of-living pressures are putting Australians in difficult economic circumstances, particularly those who may have already been feeling the squeeze before the high inflationary period following the pandemic. Using Mapping Social Cohesion data from 2024, this paper shows those who identify as struggling to pay bills or poor are struggling emotionally.

Starting in 2007 and administered each year since 2009, the Mapping Social Cohesion surveys are a unique source of data about how Australians view their lives and the communities they live in. The surveys use a systematic methodology with nationally representative samples that provide a strong basis for analysis of sub-groups. The Social Cohesion Insights series dives deeper into these rich data.

Introduction

Australians have been doing it tough the past few years. According to the January 2024 ANU poll, 34% of the Australian population were finding it difficult or very difficult to get by on their current income (Biddle et al., 2025). This follows a period of high inflation that peaked in December 2022 at 8% (ABS, 2025a), elevated cash rates (RBA, 2025), and rapid increases in housing costs following the pandemic (ABS, 2025b). In response to the rising cost of living, many Australians are not only looking to reduce their spending altogether but are also changing how they spend their money on essentials. Over 62% of Australians have altered their spending on groceries and essential purchases to ease financial strain (Biddle et al., 2025). Thus, the material impact of rising prices on Australians’ financial circumstances and decision-making has been substantial.

If many Australians are doing it tough, some of them are doing it even tougher. Rising costs of living disproportionately impact those on lower incomes or with fewer financial assets – they are not able to weather the storm of rising inflation in the same way their better-off counterparts can.

In the context of this widening gap in Australia, the experiences of those doing it tough exemplify the concerning relationship between financial and emotional distress. How have rising living costs affected Australians’ emotional well-being, and what are the implications for social cohesion in Australia?

There is a clear link between people’s financial circumstances and social cohesion. Better financial well-being is one of the factors most associated with a strong sense of belonging, strong social connections, happiness and a sense of social justice, people’s trust in one another and institutions, and their general acceptance of differences in society (O’Donnell & Guan, 2024). The better off people are financially, the better that is for social cohesion in Australia.

Looking at the groups that are suffering financially by using the Mapping Social Cohesion (MSC) Survey from 2024 (O’Donnell & Guan, 2024). This paper unpacks what it means to be ‘stretched thin’ financially, materially and emotionally, and the potential implications for social cohesion. The link between financial stress and loneliness is explored within the broader literature. Finally, the unique role of housing in financial stress is examined in the context of rising housing expenses over the last few years.

Who is suffering from financial hardship in Australia?

How are people who may be under financial stress coping? To examine this, we looked at the relevant question on financial circumstances in the 2024 MSC Survey (O’Donnell & Guan, 2024): “Which of the following terms best describes your financial circumstances:

- Prosperous,

- Living very comfortably,

- Living reasonably comfortably,

- Just getting along,

- Struggling to pay bills, or

- Poor.”

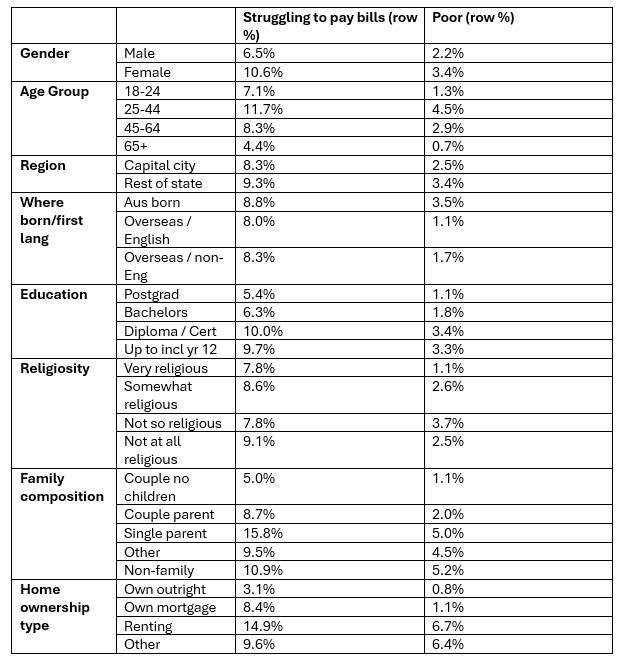

In 2024, 9% of respondents (588 respondents) identified as struggling to pay bills, while 3% identified as poor (180 respondents). The proportion of those who identified as poor only marginally increased from 2% to 3% between 2023 and 2024, while those who identified as struggling to pay bills remained stable at 9% over the same period.

A larger proportion of women identified as struggling to pay bills than men (11% compared to 7% respectively), while the proportion of men and women who identified as poor was similar. Interestingly, 15% of those who were renting identified as struggling to pay bills, while 7% of renters identified as poor. This is compared to 8% of mortgage holders who identified as struggling to pay bills, and only 1% of mortgage holders who identified as poor. 16% of single parents identified as struggling to pay bills, compared with 9% of couples with children. See Appendix 1 for more detailed sample characteristics.

Those who are poor or alienated are generally less likely to complete public opinion surveys and are likely underrepresented on probability panels such as the Life in Australia panel, which is used for the MSC surveys. This is due to a combination of barriers. Structural factors, such as digital access, housing instability or time constraints restrict peoples’ ability to access or allocate ample time to complete surveys. Those who feel socially or politically alienated may also distrust institutions, and those feeling socially isolated—something which those struggling financially experience more—are less likely to participate in public opinion surveys (Watanabe et al., 2017). Furthermore, those who are experiencing financial hardship may feel overlooked by policymakers and may not see participation in a public opinion survey a worthwhile use of their time (Yildirim & Bulut, 2023).

All this can result in nonresponse bias, where the views of those experiencing financial stress may be underrepresented. This is partially remediated with weighting, but this does not always fully account for missing perspectives.

The findings presented here and the strong relationship between emotional and financial stress are consistent with other research, including in surveys based on non-probability samples (Hassan et al., 2024; Zhan, 2022). Furthermore, by focusing specifically on those who identify as struggling to pay bills or poor this paper focuses on the views of those that can often be eclipsed by respondents in other categories.

While only 11% of respondents to the MSC survey said they were struggling to pay bills or poor, 34% of respondents to the ANUpoll stated they were finding it difficult or very difficult to get by on their current income (Biddle et al., 2025). Both the MSC survey and ANUpoll use the Social Research Centre’s Life in AustraliaTM panel, Australia’s premier representative probability based panel with over 10,000 randomly recruited members (Social Research Centre, 2025).

As will be discussed below, this could suggest that the question used by ANUpoll that explicitly asks respondents about difficulties getting by on their current income may be a better reflection of financial hardship, as opposed to the self-assessed financial situation, which could indicate overextension as opposed to hardship. Regardless, the focus on those who identify as struggling to pay bills and poor produces relevant insights into the relationship between financial situation and emotional distress.

Suffering financial hardship means prioritising basic necessities

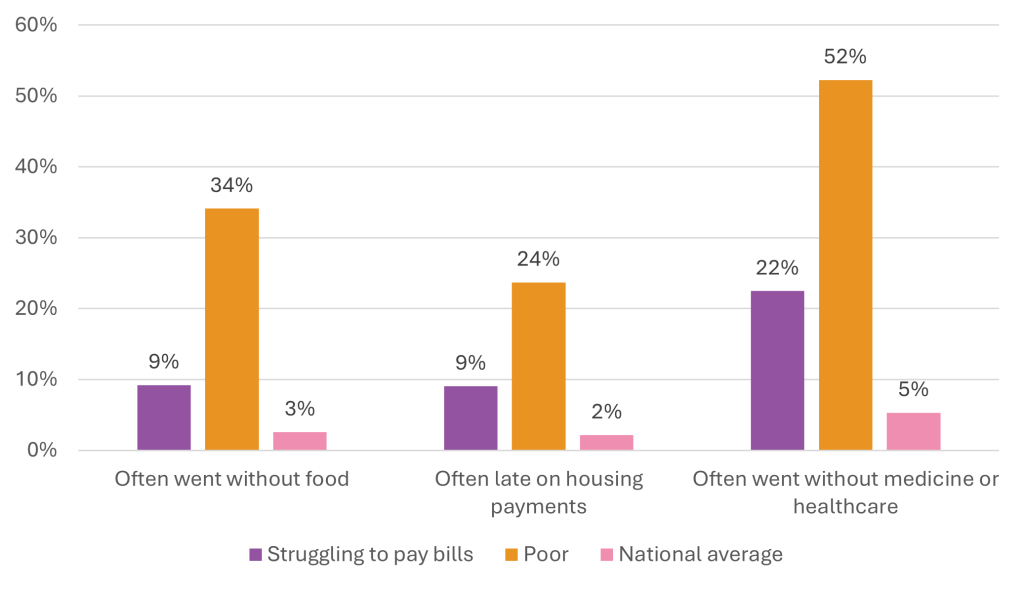

People in precarious financial circumstances often struggle to afford basic necessities, including food, housing and healthcare. However, there are notable differences even between those struggling to get by and those in more severe situations of economic deprivation. Those who identify as poor often report going without meals, being late on their housing payments, and going without medicine or healthcare at significantly higher rates than those who are struggling to pay bills. The largest difference is in medicine and healthcare, with 52% of those who are poor saying they often couldn’t pay, compared to 22% of those who are struggling to pay bills and only 5% of the sample in total saying the same.

Figure 1. Financial hardship and basic necessities, MSC 2024

Note: National average refers to the overall MSC sample.

In addition, there is a clear pattern of prioritisation, especially among those who describe themselves as poor. 52% reported that they often went without healthcare, 34% reported that they often went without food, and 24% reported that they were often late on housing payments. This prioritisation pattern is echoed in research conducted by Way Forward Debt Solutions, a small Australian not-for-profit organisation that assists people in hardship to get out of debt. Their 2023 client survey, of which all in the sample are in financial stress and on debt management plans, found that housing is always first on the list of spending priorities, and this comes at the expense of everything else (Way Forward, 2023).

Housing

Access to safe, affordable housing is an important piece of the puzzle – as previously discussed, when people are under financial stress, housing payments take priority, often at the expense of other essential items (Naidoo et al., 2024; Way Forward, 2023). The impacts of housing on financial stress are multifaceted, but two aspects discussed here include housing as a driver of wealth inequality; and housing as a major expense for those who are not outright owners.

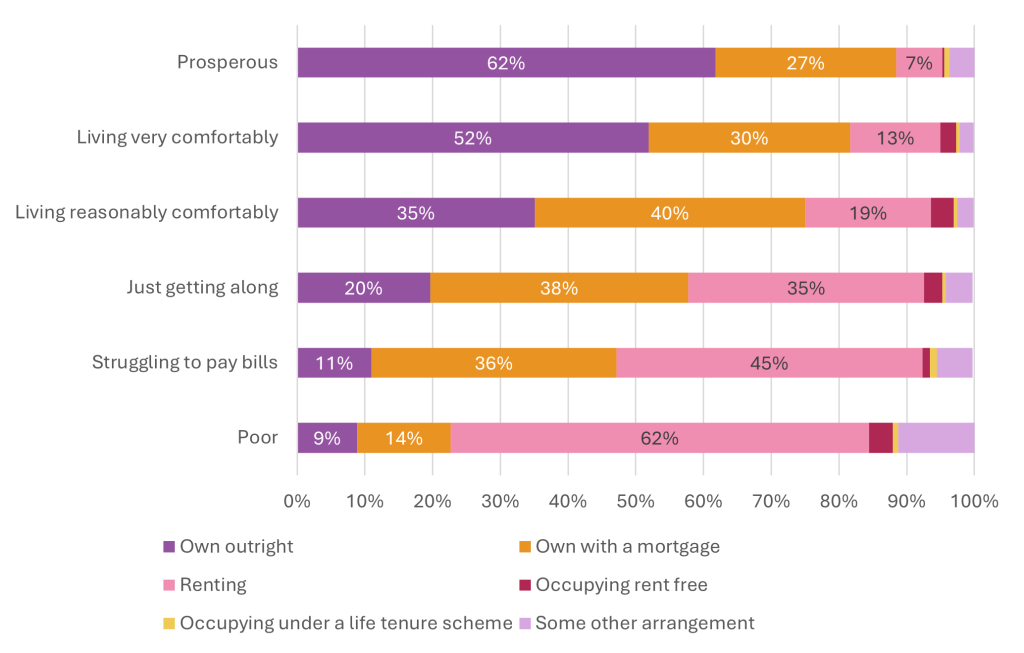

A large portion of wealth inequality (38%) in 2024 was a result of the unequal distribution of housing, as reported by the Australian Council of Social Services and UNSW (2024). Average wealth from 2003 to 2022 grew by 74%, however 45% of this went to the wealthiest 10% of households (Australian Council of Social Services & UNSW, 2024). The link between housing and financial situation holds when looking at MSC data – those who identify as ‘prosperous’ or ‘living very comfortably’ are significantly more likely to own their home outright, while those who are ‘poor’ are significantly more likely to rent than any other group.

Figure 2. Housing tenure by financial situation, MSC 2024

Note: Data labels only shown for three largest categories. Categories may not add up to 100% where there are missing cases.

Housing is a large outgoing cost for households who do not own outright. While only 0.3% of outright owners were spending more than 30% of their disposable income, this figure rises to 28% for renters and 45% of owners with a mortgage (AIHW, 2025).

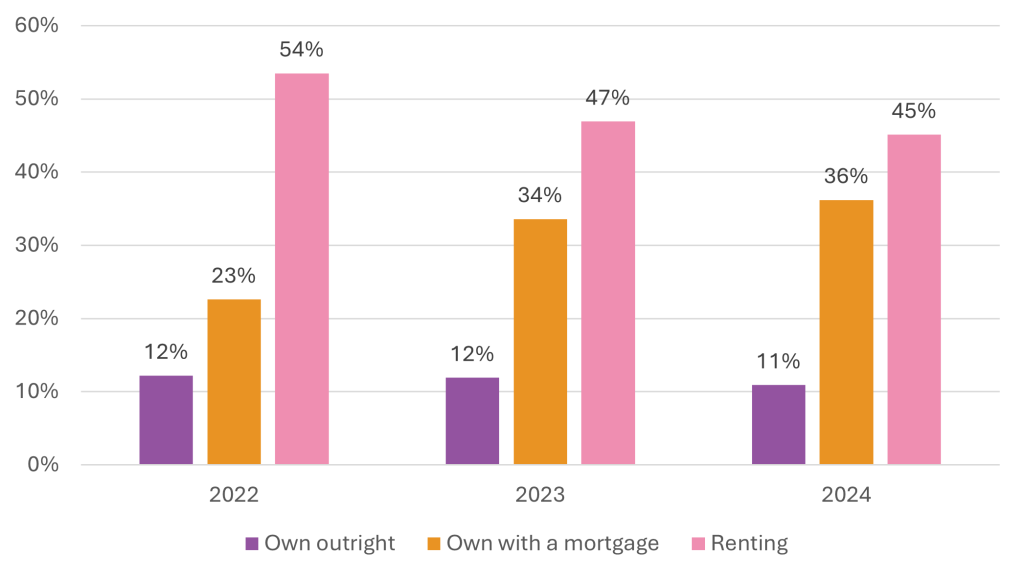

Interestingly, those who are struggling to pay bills are significantly more likely to have a mortgage. This may be a result of the fact that high inflation hit mortgage holders particularly hard, as the RBA increased cash rates from mid-2022 onwards to counteract rising inflation. The proportion of people who hold a mortgage and are struggling to pay the bills increased from 5% in 2022 to 9% in 2023.

While mortgage interest charges did increase 92% in the 12 months to June 2023 (at its peak), there are other macroeconomic factors at play (ABS, 2025b). During the COVID-19 pandemic, when interest rates were at historically low levels, people took out larger mortgages, oftentimes on fixed interest rates for a period of roughly 3 to 5 years. The subsequent increase in cash rates from 2022 onwards, and the expiry of these fixed-rate mortgages, meant that those with mortgages started feeling the squeeze on their household budgets. In other words, while the increased mortgage payments mean that more people are struggling to pay bills, in some cases, this may the result of overextension to be competitive in Australia’s housing markets.

Figure 3. Housing tenure of those struggling to pay bills, MSC 2022 – 2024

While the proportion of renters who identified as struggling to pay bills declined from 54% in 2022 to 45% in 2024, 62% of renters identified as poor in 2024, stable from 61% in 2022. Renters tend to have lower incomes and lower wealth, making them more vulnerable to rising rents and cost-of-living pressures (Agarwal et al., 2023).

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) reported that in 2024-25, 21% of households in the rental market were low-income households in financial stress, compared to home-owners with a mortgage (15%) and outright owners (0.3%) (AIHW, 2025). This also highlights the vulnerability of those who rent, as they do not have any financial assets that they could turn to in times of serious financial difficulties.

Suffering financial hardship has a heavy emotional toll

Referring to the hardship questions in Figure 1, healthcare taking a lower priority for those in financially difficult circumstances is a reason for concern. People’s inability to afford proper health care can lead to a further decline in their financial circumstances, as poor health can increase the likelihood of experiencing financial stress, as it can affect people’s ability to work (Callander et al., 2019). The inability to afford appropriate healthcare is particularly problematic because financial stress is also associated with poorer mental health (Chai et al., 2025).

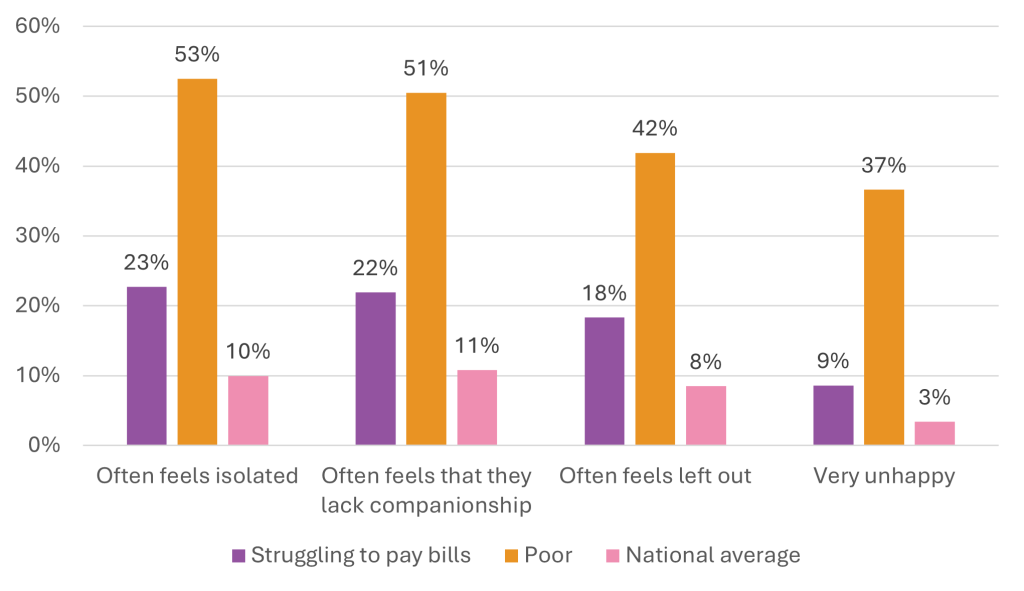

Figure 4. Experiences of emotional distress, MSC 2024

While only 3% of the MSC sample state they are very unhappy, 9% of those who are struggling to pay bills and 37% of those who are poor say the same. Furthermore, our findings show that those who are struggling to pay bills or poor deal with a heavy emotional toll: feeling socially isolated. About 53% of those who are poor often feel isolated from others, compared to 23% of those who are struggling, while the national average only sits at 10%. Of those who identify as poor, 51% often feel they lack companionship and 42% often feel left out, compared to 22% and 18% respectively of those who are struggling to pay bills.

There is a strong correlation between financial strain and loneliness (Bierman et al., 2024; Chai et al., 2025; Drost et al., 2024). Those who are in lower income deciles are more likely to feel lonely and experience the associated adverse side effects of pain, fatigue, and low mood compared to their wealthier counterparts, despite no differences in reported time spent socialising (Davis et al., 2025). There is evidence to suggest that the experience of poverty can impact how individuals experience social connections and support, rather than socialising having the same mitigating impact across all socioeconomic groups (Davis et al., 2025). Loneliness is influenced by factors beyond the frequency of socialising, and rather represents a discrepancy between an individual’s social needs and what their social worlds can provide (Davis et al., 2025). Limitations on economic resources and time restricts individuals’ access to leisure activities, and impacts the ability to experience meaningful connection (Lubbers et al., 2020). The context (both personal and societal) in which individuals socialise may impact the extent to which social relationships engender a sense of connectedness and belonging (Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015).

One of these effective forms of socialising for those in financial stress is active community engagement and a strong sense of belonging in their neighbourhood. When respondents were engaged in community support groups or had a strong sense of belonging to their neighbourhood, this had a moderating impact on the emotional toll of financial stress.

In the MSC 2024, being actively involved in community support groups brings those who are struggling to pay bills that often feel isolated down to 18%, rather than the 24% without involvement in community support groups. Similarly, 44% of those who are poor often feel isolated when they are involved in community support groups, compared to 56% who weren’t involved.

Neighbourhood belonging seems to have a similar moderating role in reducing emotional distress. Only 16% of those who are struggling that also agree or strongly agree they belong in their neighbourhood often feel isolated, compared to 37% of those who disagree or strongly disagree that they belong. For those who are poor, sense of belonging did not seem to impact feelings of isolation significantly, likely due to sample size. Further analysis into other types of engagement and support would be useful to understand more about the insulating role of socialising against emotional distress for those experiencing financial stress.

Conclusion

The cost of financial stress is evident – people who identify as struggling to pay bills or poor tend to express signs of emotional distress at significantly higher levels than the national average. Furthermore, the strong correlation between financial stress and emotional distress highlights a vulnerable group in Australian society that may be falling through the healthcare system gaps as they struggle to pay for medicine and healthcare. Future research could investigate the insulative role of neighbourhood cohesion that may mitigate the impact of financial stress on loneliness. Access to sufficient financial and mental health support is vital for those doing it tough in Australia, or we risk further entrenching inequality.

The health outcomes of individuals experiencing financial stress and loneliness is not in scope for this paper. The effect of financial stress on mental health partially operates through loneliness (Chai et al., 2025). Investigating the findings presented in this paper alongside mental health outcomes may be useful research in extrapolating this link in the Australian context and identify particularly vulnerable populations to the adverse impacts of poor mental health.

However, social cohesion is not just a one-to-one reflection of financial circumstances – emotional and practical support through friendships and social connection can ease the burden of financial hardship on personal wellbeing and happiness. To put it simply, social cohesion can mitigate the impacts of financial hardship.

Appendix 1 – Sample characteristics

References

ABS. (2025a, April 30). Consumer Price Index, Australia, March Quarter 2025 | Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/price-indexes-and-inflation/consumer-price-index-australia/latest-release

ABS. (2025b, August 6). Selected Living Cost Indexes, Australia, June 2025 | Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/price-indexes-and-inflation/selected-living-cost-indexes-australia/latest-release

Agarwal, N., Gao, R., & Garner, M. (2023, March). Renters, Rent Inflation and Renter Stress. RBA Bulletin. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2023/mar/renters-rent-inflation-and-renter-stress.html

AIHW. (2025, July 15). Housing affordability. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/housing-affordability

Australian Council of Social Services, & UNSW. (2024, April). Inequality in Australia 2024: Who is affected and how. Australian Council of Social Services.

Biddle, N., Gray, M., & Phillips, B. (2025, May 7). It’s the economy (and housing), stupid: Views of Australians on the economy and the housing market in January 2024. POLIS@ANU: The Centre for Social Policy Research.

Bierman, A., Upenieks, L., Lee, Y., & Mehrabi, F. (2024). Mattering and Self-Esteem as Bulwarks Against the Consequences of Financial Strain for Loneliness in Later Life: Differentiating Between- and Within-Person Processes. Research on Aging, 46(3–4), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/01640275231221326

Callander, E. J., Fox, H., & Lindsay, D. (2019). Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in Australia: Trends, inequalities and the impact on household living standards in a high-income country with a universal health care system. Health Economics Review, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-019-0227-9

Chai, L., Wang, S., & Lu, Z. (2025). The role of loneliness in mediating the relationship between financial strain and mental health: Exploring gender differences in a UK longitudinal study. Public Health, 242, 299–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2025.03.008

Davis, A. J., Cohen, E., & Nettle, D. (2025). Associations amongst poverty, loneliness, and a defensive symptom cluster characterised by pain, fatigue, and low mood. Public Health, 242, 272–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2025.02.037

Drost, M. A., Snyder, A. R., Betz, M., & Loibl, C. (2024). Financial strain and loneliness in older adults. Applied Economics Letters, 31(9), 845–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2022.2152421

Hassan, M., Fang, S., Rizwan, M., Malik, A. S., & Mushtaque, I. (2024). Impact of Financial Stress, Parental Expectation and Test Anxiety on Role of Suicidal Ideation: A Cross-Sectional Study among Pre-Medical Students. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 26(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.043096

Hawkley, L. C., & Capitanio, J. P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140114. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114

Lubbers, M. J., García, H. V., Castaño, P. E., Molina, J. L., Casellas, A., & Rebollo, J. G. (2020). Relationships Stretched Thin: Social Support Mobilization in Poverty. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 689(1), 65–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220911913

Naidoo, Y., Wong, M., Smyth, C., & Davidson, P. (2024). Material deprivation in Australia: The essentials of life. UNSW Sydney. https://doi.org/10.26190/UNSWORKS/30746

O’Donnell, J., & Guan, Q. (2024). Mapping Social Cohesion 2024. Scanlon Foundation Research Institute.

RBA. (2025). Cash Rate Target. Reserve Bank of Australia. https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/cash-rate/index.html

Social Research Centre. (2025). Life in AustraliaTM. https://srcentre.com.au/lifeinaustralia/

Watanabe, M., Olson, K., & Falci, C. (2017). Social isolation, survey nonresponse, and nonresponse bias: An empirical evaluation using social network data within an organization. Social Science Research, 63, 324–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.09.005

Way Forward. (2023). Under Pressure: How people prioritise spending in a cost-of-living crisis. https://wayforward.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Building-Financial-Resilience.pdf

Yildirim, T. M., & Bulut, A. T. (2023). Income inequality and opinion expression gap in the American public: An analysis of policy priorities. Journal of Public Policy, 43(1), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X22000253

Zhan, M. (2022). Financial Stress and Hardship among Young Adults: The Role of Student Loan Debt. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 49(3). https://doi.org/10.15453/0191-5096.4541