This edition of Social Cohesion Insights explores the notion of happiness and its relationship to social cohesion. Are socially cohesive societies happier? Or does happiness lead to greater social cohesion?

Starting in 2007 and administered each year since 2009, the Scanlon Foundation surveys are a unique source of data about how Australians view social cohesion issues. The surveys use a systematic methodology with large samples that provide a strong basis for analysis of sub-groups. The Social Cohesion Insights series digs deeper into the findings, and provides added context, explanation, and commentary.

Download PDF version here.

What is happiness?

Happiness isn’t an easy concept to define. While some theorists simply consider it an emotion “associated with pleasure or joy,”[1] others argue happiness consists of both “feelings” and a more “enduring condition” or “state.”[2] Shin and Johnson (1978), for example, argue that happiness shouldn’t be confused with feelings of pleasure or elation. Instead, it should be understood more broadly as an “evaluation of [an] individual’s life quality.”[3] In this sense happiness shouldn’t be considered an emotion but a “subjective measure” of a person’s “quality of life.”[4]

Theorists who define happiness in this way often use it as an “umbrella term” for the notion of a good life. It is often used synonymously with terms like ‘quality of life’[5] or ‘well-being.’[6]

The pursuit of happiness

Questions of what a good life consists of (and how to attain one) has long been of interest to philosophers and others. In recent history, eighteenth and 19th century protagonists like Jeremy Bentham and Immanuel Kant are well known for their attempts to describe the ideal conditions of human existence, and they developed lists of qualities and conditions they believed would lead to ultimate human purpose, fulfillment and pleasure.

These questions have also preoccupied psychologists and sociologists. In the twentieth century, a growing body of research focused on understanding and determining what contributes to our quality of life and wellbeing.[7]

Moving forward to the 1970s, a new group of theorists would enter the happiness research field: economists. [8]

Happiness economics

Traditionally, economic growth has been considered a primary marker of progress. Governments have sought to make their countries richer, based on the underlying assumption that “greater wealth is good for people.”[9] For a long time, economic growth as a central policy focus was not questioned. However, more recently, that has begun to change. A new (or renewed [10]) school of thought suggests that progress means improved quality of life,[11] and this means governments should focus on a range of indicators that are broader than “traditional macroeconomic measures.”

This approach to economic policy and the allocation of budgetary resources has been a key pillar of the federal treasurer’s wellbeing approach. Jim Chalmers argues:

countries over time, providing individual responses to various indicators, as well as a general indication of their happiness. Such surveys typically use questions like “Generally speaking, how happy are you with your life.” or “How satisfied are you with your life,” where individuals can respond using a pre-determined scale.

How happy are Australians?

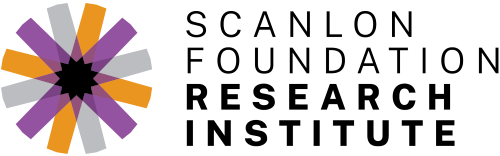

Like many of these surveys, the MSC survey asks individuals to rate their happiness on a scale. It asks: “Taking all things into consideration, would you say that over the last year you have been very happy, happy, unhappy, or very unhappy?”

The 2022 results reveal that levels of happiness in Australia remain high (Figure 1.). Seventy-seven per cent of respondents reported that they were happy or very happy, a result that has remained relatively consistent since 2018. Thirteen per cent of people indicated they are very happy, the same proportion as in 2019.

These results are consistent with other happiness research. For instance, the most recent World Happiness Report, produced by the United Nations' Sustainable Solutions Network since 2012, ranked Australia as the 12th happiest place in the world (based on respondents’ reported life satisfaction.)[15]

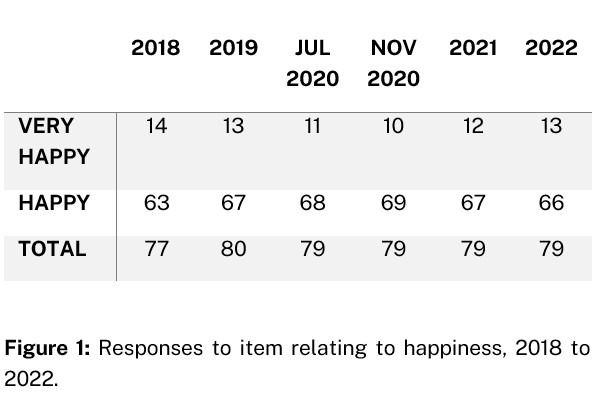

Australia’s World Happiness survey results over time show most respondents have indicated they feel ‘very happy’ or ‘quite happy’ since 1981 (Figure 2.).

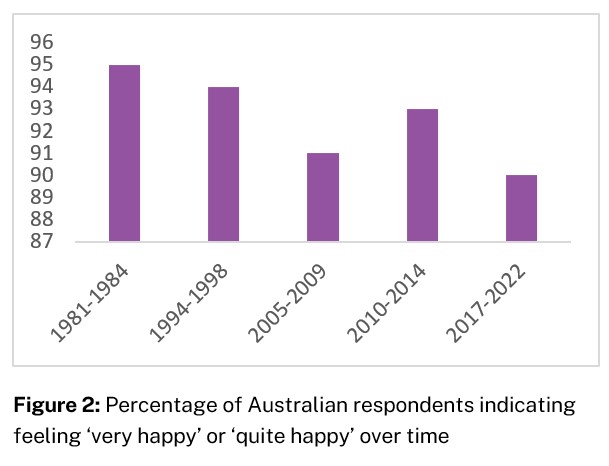

Overall, Australia ranks very consistently with other ‘happy’ countries around the world, with 90 per cent of people indicating they feel ‘very happy’ or ‘quite happy’ on the survey between 2017 and 2022 (Figure 3.)

What makes people happy?

Looking more closely at the MSC survey data, we can see differences in happiness among certain groups. Older people—those aged 65 years and older—rated themselves as much happier than those in the younger age groups. Those who were born overseas or for whom English is not their first language reported being much less happy in 2022 in comparison to previous years (down from 86 per cent in 2018, to 80 per cent in July 2020 and 76 per cent in 2022).

One influencer of happiness appears to be an individual’s financial situation. Those who reported feeling financially comfortable reported greater happiness than those who were struggling. In 2022, 41 per cent of people who said they were poor or struggling to pay their bills also said they were happy or very happy, compared with those who described themselves as prosperous or very comfortable (94 per cent) or reasonably comfortable (88 per cent). Other studies also suggest that “a poor financial condition” can be a “primary factor behind unhappiness.”[16]

Those who feel pessimistic about the future or who worry about losing their job also report substantially lower levels of happiness.

European researchers argue that just as economists are interested in the distribution of income inequality, they should also be concerned about how happiness is distributed in society. This is because differences in life satisfaction can be a source of social tension between individuals or groups.[17]

Happiness and social cohesion

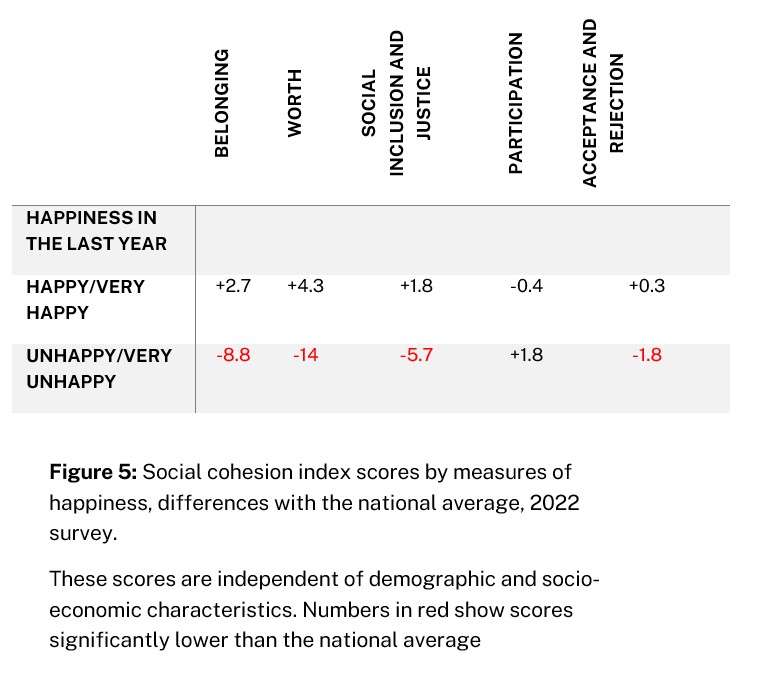

The MSC survey reveals happiness is strongly related to elements of social cohesion. The following table (Figure 5.) shows scores for each of the five domains of the Scanlon-Monash Index in comparison to the national average for those who rated themselves as happy/very happy or unhappy/very unhappy in the last year.

Those people who reported being unhappy or very unhappy had lower scores on the Belonging domain, the domain that measures the extent to which people feel personally accepted, respected, included and supported by others. Their average scores of belonging were almost nine points lower than the national average (12 points lower than people who are happy or very happy). A similar trend can be seen when looking at other domains. Those who reported unhappiness had scores that were almost six points below the national average in terms of social inclusion and justice (which measures the extent to which people feel that social, economic, and political opportunities and outcomes are fair and equitable) and almost two points below in terms of acceptance and rejection (the lived reality of social cohesion).

What is the connection between happiness and social cohesion? There are several reasons why happiness may be closely connected to social cohesion. On one hand, people who are happy and well connected in their personal lives are perhaps more likely to have positive perceptions of a country’s cohesiveness more generally. On the other hand, the feelings of belonging, social connectedness and stability that come from living in a cohesive society may contribute to individuals feeling happier.

Which comes first: social cohesion or happiness?

It is currently unclear whether social cohesion creates the conditions necessary for happiness or whether the happiness of individuals contributes to a country’s social cohesion.

One study that considers this question was conducted in 2016 by European researchers Jan Delhey and Georgi Dragolov. Using data from the European Quality of Life Survey for 27 European Union countries and the Bertelsmann Cohesion Index,[18] they found that Europeans are happier (and psychologically healthier) in more cohesive societies.[19] They argued that social cohesion contributes to happiness because it is a “crucial societal condition” for a positive evaluation of life and for a person’s subjective well-being. This is because:

It is currently unclear whether social cohesion creates the conditions necessary for happiness or whether the happiness of individuals contributes to a country’s social cohesion.

One study that considers this question was conducted in 2016 by European researchers Jan Delhey and Georgi Dragolov. Using data from the European Quality of Life Survey for 27 European Union countries and the Bertelsmann Cohesion Index,[20] they found that Europeans are happier (and psychologically healthier) in more cohesive societies.[21] They argued that social cohesion contributes to happiness because it is a “crucial societal condition” for a positive evaluation of life and for a person’s subjective well-being. This is because:

However, “discontent” and “expected utility” theories argue the opposite. They suggest that those people who are unhappier and have lower levels of life satisfaction are more likely to contribute to social unrest. For those who feel envious of others whom they perceive to have more than them (whether in terms of income or opportunities for achievement or close relationships), the expected gain of “rebellious actions” is higher than the cost.[22]

Other happiness research reveals interesting relationships between elements of social cohesion and happiness. For instance, a 1990s study found that happiness is more equally distributed in countries that are more “economically stable and developed.” [23] Some years later, another study suggested that people tend to be happier in countries with “good government.”[24]

While it appears that social cohesion may be an important contextual condition[25] and “collective resource” for quality of life,[26] more research will need to be conducted to determine the exact nature of the relationship between happiness and social cohesion.

The implications of happiness research for Australia

Australia is a happy country. It has been consistently ranked as one of the happiest places in the world. The MSC surveys reveal that happiness levels remain high and have been so for some time. This suggests that Australia is currently well positioned in terms of “non-market” measures of economic progress.

However, there are some caveats. Happiness is not universally experienced across Australia. There are some groups who report much lower levels of happiness. The fact that those who speak English as a second language or who were born overseas report lower levels of happiness should be a cause for concern and examination.

We also know there is a relationship between financial satisfaction and happiness. Those who are struggling financially are less happy. As Australia enters increasingly uncertain economic times and cost of living pressures are rising, including the number of Australians struggling to pay their bills, will we begin to see this impact on Australians’ reported happiness? We know, more broadly, that those who report to be struggling financially report lower levels of belonging, personal well-being and social inclusion and justice—key elements of social cohesion.

The relationship between happiness and social cohesion is currently unclear. It appears social cohesion may be a precursor for happiness, yet happiness may also impact social cohesion. The nature of this dynamic (and any changes in reported levels of happiness or of social cohesion) should be of interest to researchers and policy makers alike.

Looking forward, Australia has adopted a notion of progress beyond traditional measures of economic success. Like other governments around the world,[27] the federal government has expressed commitment to measure and explore those factors that contribute to Australians’ well-being and quality of life. ‘Measuring what matters’ will become increasingly important in a national and international context in which social and economic pressures have the potential to undermine Australians’ happiness. A country’s success can be judged by the happiness of its people[28] and Australia has a long record of achievement in this regard. With targeted measures to ensure contemporary threats are mitigated and happiness is within reach of all, Australians can look forward to a quality of life that remains enviable internationally.

Bibliography

Becchetti, Leonardo, Massari, Riccardo and Naticchioni, Paolo, “Why has Happiness Inequality Increased? Suggestions for Promoting Social Cohesion.” (2011) Working Papers 177, ECINEQ, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality. Available https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=e7f5e993cb0e22bd977f825081f0b0b75ca2fbf2.

Centre for Policy Development, “Redefining Progress: Global Lessons for Australia’s Approach to Wellbeing.” (2022) Available https://cpd.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/CPD-Redefining-Progress-FINAL.pdf.

Coch, Lukas, “Chalmers Hasn’t Delivered a Wellbeing Budget, but it’s a Step in the Right Direction.” The Conversation, 26 October 2022. Available https://theconversation.com/chalmers-hasnt-delivered-a-wellbeing-budget-but-its-a-step-in-the-right-direction-192840.

Colman, A. ‘Happiness.’ (2015) A Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coyle, Diane, ‘Happiness.’ In Diane Coyle, Happiness: The Economics of Enough. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Delhey, Jan and Dragolov, Georgi, “Happier Together: Social Cohesion and Subjective Well-Being in Europe.” (2016) International Journal of Psychology, 163-176.

Klein, Carlo, “Social Capital or Social Cohesion.” (2013) 110 Social Indicators Research, 891-911.

Majumdar, Chirodip and Gupta, Gautam, “Don’t Worry Be Happy: A Survey of Economic Happiness.” (2015) 50(40) Economic and Political Weekly, 50-62.

Medvedev, O.N. and Landhuis, C.E., “Exploring Constructs of Well-Being, Happiness and Quality of Life.” (2018) PeerJ. Available online https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5985772.

Nancarrow, Dan and Stuart, David, “The 2023 World Happiness Report Has Been Released. Where Does Australia Rank and What Makes a Country 'Happy'?” ABC News, 21 March 2023. Available

Veenhoven, Ruut, “Co-Development of Happiness Research.” (2018) 135(3) Social Indicators Research, 1001-1007.

World Happiness Report. Available https://worldhappiness.report.

References

[1] A. Colman, ‘Happiness.’ (2015) A Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[2] O.N. Medvedev and C.E. Landhuis, “Exploring Constructs of Well-Being, Happiness and Quality of Life.” (2018) PeerJ. Available online https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5985772.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Chirodip Majumdar and Gautam Gupta, “Don’t Worry Be Happy: A Survey of Economic Happiness.” (2015) 50(40) Economic and Political Weekly, 50.

[5] Ruut Veenhoven, “Co-Development of Happiness Research.” (2018) 135(3) Social Indicators Research, 1002.

[6] O.N. Medvedev and C.E. Landhuis, (2018). “Exploring Constructs of Well-Being, Happiness and Quality of Life.” (2018) PeerJ. Available online https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5985772.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Chirodip Majumdar and Gautam Gupta, “Don’t Worry Be Happy: A Survey of Economic Happiness.” (2015) 50(40) Economic and Political Weekly, 50. Pioneering work in this regard is considered to have been conducted by Easterlin (1973, 1974).

[9] Diane Coyle, ‘Happiness.’ In Diane Coyle, Happiness: The Economics of Enough. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 22.

[10] Centre for Policy Development, “Redefining Progress: Global Lessons for Australia’s Approach to Wellbeing.” (2022) Available https://cpd.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/CPD-Redefining-Progress-FINAL.pdf, 8.

[11] Ibid., 6.

[12] Lukas Coch, “Chalmers Hasn’t Delivered a Wellbeing Budget, but it’s a Step in the Right Direction.” The Conversation, 26 October 2022. Available https://theconversation.com/chalmers-hasnt-delivered-a-wellbeing-budget-but-its-a-step-in-the-right-direction-192840.

[13] Carlo Klein, “Social Capital or Social Cohesion.” (2013) 110 Social Indicators Research, 891.

[14] Jan Delhey and Georgi Dragolov, “Happier Together: Social Cohesion and Subjective Well-Being in Europe.” (2016) International Journal of Psychology, 163.

[15] Dan Nancarrow and David Stuart, “The 2023 World Happiness Report Has Been Released. Where Does Australia Rank and What Makes a Country 'Happy'?” ABC News 21 March, 2023. Available https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-03-21/finland-worlds-happiest-nation-world-happiness-report-2023/102124044. These life evaluations ask survey respondents to evaluate their current life, from 0 to 10, in comparison to the life they'd ideally like to be living

[16] Chirodip Majumdar and Gautam Gupta, “Don’t Worry Be Happy: A Survey of Economic Happiness.” (2015) 50(40) Economic and Political Weekly, 55.

[17] Leonardo Becchetti, Riccardo Massari and Paolo Naticchioni, “Why has Happiness Inequality Increased? Suggestions for Promoting Social Cohesion.” (2011) Working Papers 177, ECINEQ, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality. Available https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=e7f5e993cb0e22bd977f825081f0b0b75ca2fbf2, 2. See, for instance, G. Tullock, “The Paradox of Revolution.” (1971) 11 Public Choice, 89–100; Michael E. Brown, “The Causes and Regional Dimensions of Internal Conflict” in Michael Brown (ed.) The International Dimensions of Internal Conflict (1996). Cambridge,

[18] MA: MIT Press; Ted R. Gurr, “Peoples Against States: Ethnopolitical Conflict and the Changing World System.” (1994) 38 International Studies Quarterly, 347-377.

[19] This index consists of three domains: Connectedness, Social Relations and Focus on the Common Good.

[20] Jan Delhey and Georgi Dragolov, “Happier Together: Social Cohesion and Subjective Well-Being in Europe.” (2016) International Journal of Psychology, 163.

[21] Ibid., 164.

[22] Leonardo Becchetti, Riccardo Massari and Paolo Naticchioni, “Why has Happiness Inequality Increased? Suggestions for Promoting Social Cohesion.” (2011) Working Papers 177, ECINEQ, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality. Available https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=e7f5e993cb0e22bd977f825081f0b0b75ca2fbf2, 6. See G. Tullock, “The Paradox of Revolution.” (1971) 11 Public Choice, 89–100.

[23] Ibid., 4.

[24] Ibid. See R. Veenhoven, “Inequality in Happiness, Inequality in Countries Compared between Countries.” (1990) Paper presented at the 12th Work Congress of Sociology, Madrid, Spain; R. Veenhoven, “Return of Inequality in Modern Society? Test by Dispersion of Life-Satisfaction Across Time and Nations.” (2005) 6(4) Journal of Happiness Studies, 457-487 and J.C. Ott, “Greater Happiness for a Greater Number: Some Non-Controversial Options for Governments.” (2010) 11(5) Journal of Happiness Studies, 631-647.

[25] Jan Delhey and Georgi Dragolov, “Happier Together: Social Cohesion and Subjective Well-Being in Europe.” (2016) International Journal of Psychology, 163.

[26] Ibid., 164.

[27] Lukas Coch, “Chalmers Hasn’t Delivered a Wellbeing Budget, but it’s a Step in the Right Direction.” The Conversation, 26 October 2022. Available https://theconversation.com/chalmers-hasnt-delivered-a-wellbeing-budget-but-its-a-step-in-the-right-direction-192840.

[28] World Happiness Report. Available https://worldhappiness.report.