Administered each year since 2007, the Mapping Social Cohesion (MSC) survey is a unique source of knowledge about how Australians view social cohesion issues. This Social Cohesion Insights series digs deeper on the findings of the survey, providing added context, explanation and commentary.

The government, social inclusion and justice during the pandemic

Social inclusion and justice is one of the five core domains of the Scanlon-Monash Index (SMI) of social cohesion. It measures survey participants’ views on national priorities including government welfare, income inequality, economic opportunities, trust in the Australian Government, and perceptions of corruption, fair elections and the rule of law.

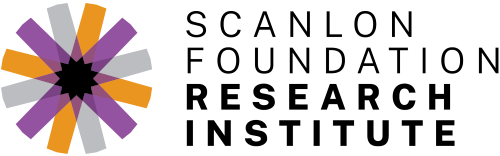

Scores in the social inclusion and justice domain of the SMI spiked after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, rising from 92.6 to 112 index points between 2019–July 2020.[1] With COVID-19 still the main topic on most Australians’ minds, this finding reflected a broadly positive assessment both of the federal government’s handling of the issue in 2020 and the capacity of our public institutions to ‘do the right thing’ in a crisis.[2]

However, scores on the social inclusion and justice index fell dramatically by 14.6 index points just one year later (see Figure 1).[3] The July 2021 survey saw a fall in positive views of the government, with interviews across the country suggesting that participants believed that state governments were now playing the most important role in responding to the pandemic.

Figure 1. Social Inclusion and Justice (Domain 3) of the Scanlon-Monash Index (SMI) of Social Cohesion, 2018–21

Attitudes and political party preference

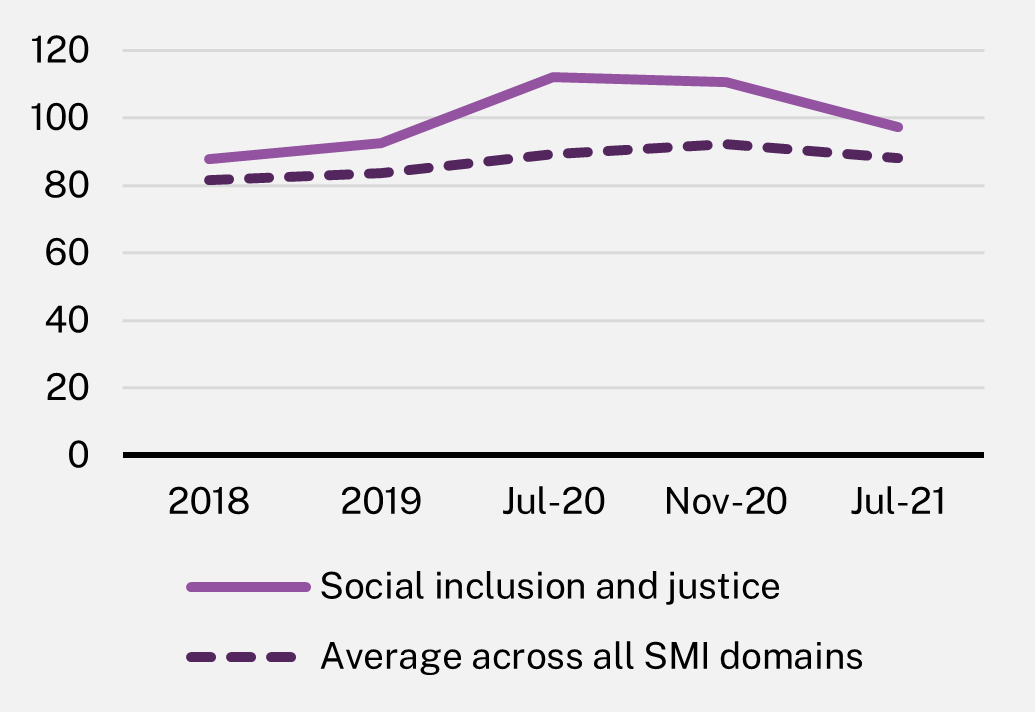

A closer look reveals that the range of participants’ opinions on social inclusion and justice issues was also sharply divided along political party lines. Voting intention (measured by the question, ‘If there was a Federal Election today, for which party would you probably vote?’) was the most important predictor of individual views within the social inclusion and justice domain—even more important than participants’ financial circumstances.[4] The 2021 index scores were highest for those who intended to vote for Coalition parties, and lower for those who intended to vote for any other party, as well as those not intending to vote (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Social Inclusion and Justice scores by voting intention (party), 2021

Levels of trust in the federal government to ‘do the right thing for the Australian people’ were also highest amongst Coalition voters, and lower amongst Greens and One Nation voters.

It may not be surprising that Coalition voters in the MSC survey were more supportive of the Coalition government than people who were intending to vote for another party. But does support for the party that forms government also drive people’s beliefs about the fairness and adequacy of current government support?

Government support for people on low incomes

Australians’ views on levels of government support (or welfare) are a core part of the MSC Social Inclusion and Justice index.

The primary forms of government welfare spending in Australia are means-tested income support payments. The goals of such policies are framed in terms of addressing income inequality encouraging ‘self-sufficiency,’ promoting full participation and enhancing personal and family wellbeing.[5]

Almost one-quarter (24%) of people over the age of 16 were receiving some form of government payment in June 2019.[6] Government financial support was also the main source of income for nearly two-thirds (65%) of the lowest-income households in Australia in the years prior to the pandemic.[7] As COVID-related public health orders began to affect employment and business activity across Australia, the federal government introduced temporary payments such as the JobKeeper Payment and Coronavirus Supplement to support people through a challenging economic and social period.

Following the introduction of these measures, the proportion of adults receiving government payments rose to 28% in June 2020. By March 2021, this proportion was still at 27%. There were an additional 5.5 million payment recipients in Australia in March 2021 compared to levels one year earlier.[8]

Are payments adequate (and fair)?

Views on ‘who should get what, and why’ help us to understand how citizens and governments assess the adequacy and fairness of the welfare system.[9] Policymakers might ask: are payments adequate to help people on low incomes become ‘self-sufficient’? Can we afford them? And do recipients deserve this support—is there actual, objective need, and the potential for reciprocity through work or taxation?[10]

Such questions are also at the heart of different political positions on government welfare. In the opening press conference of the 2019 federal election campaign, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said:

“I believe in a fair go for those who have a go, and what that means is part of the promise that we all keep as Australians is that we make a contribution and don’t seek to take one… So under our policies, if you’re having a go you’ll get a go. And that involves an obligation on all of us to be able to bring what we have to the table.”[11]

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, questions of adequacy, fairness and ‘having a go’ have become more heightened.

Public attitudes towards welfare

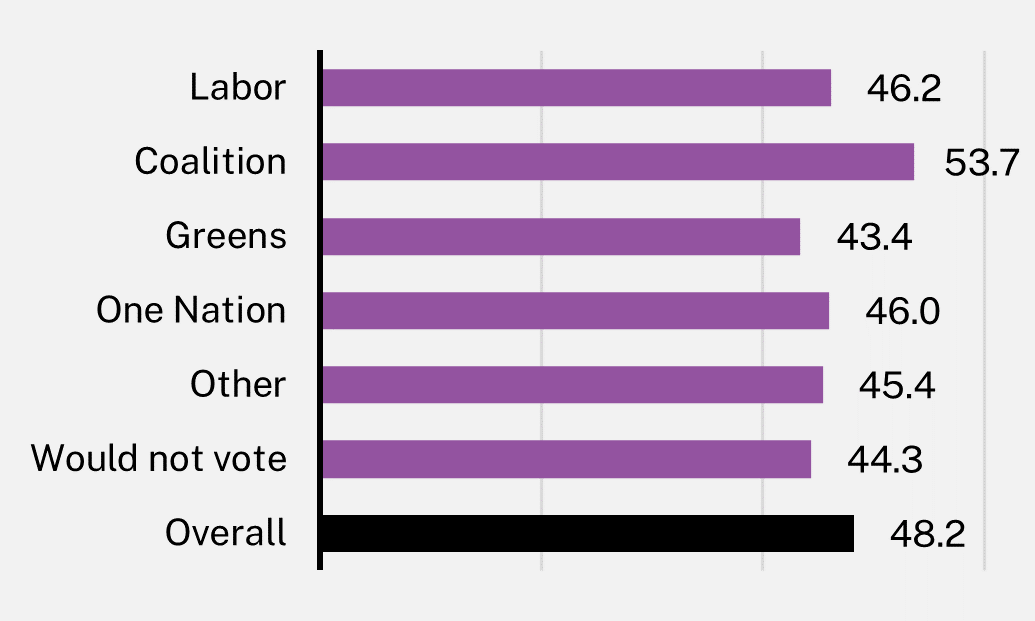

The MSC survey asks respondents to indicate the extent to which they agree with the statement, ‘People living on low incomes in Australia receive enough financial support from the government’.

In the year before the pandemic, a majority (59%) of respondents thought government support for people on low incomes was inadequate (see Figure 3). In 2020, after the federal government introduced more support measures, the balance of opinion shifted towards majority (54%) agreement. By 2021, views on welfare adequacy were more balanced: 48% agreed and 52% disagreed that those on low incomes received enough support.

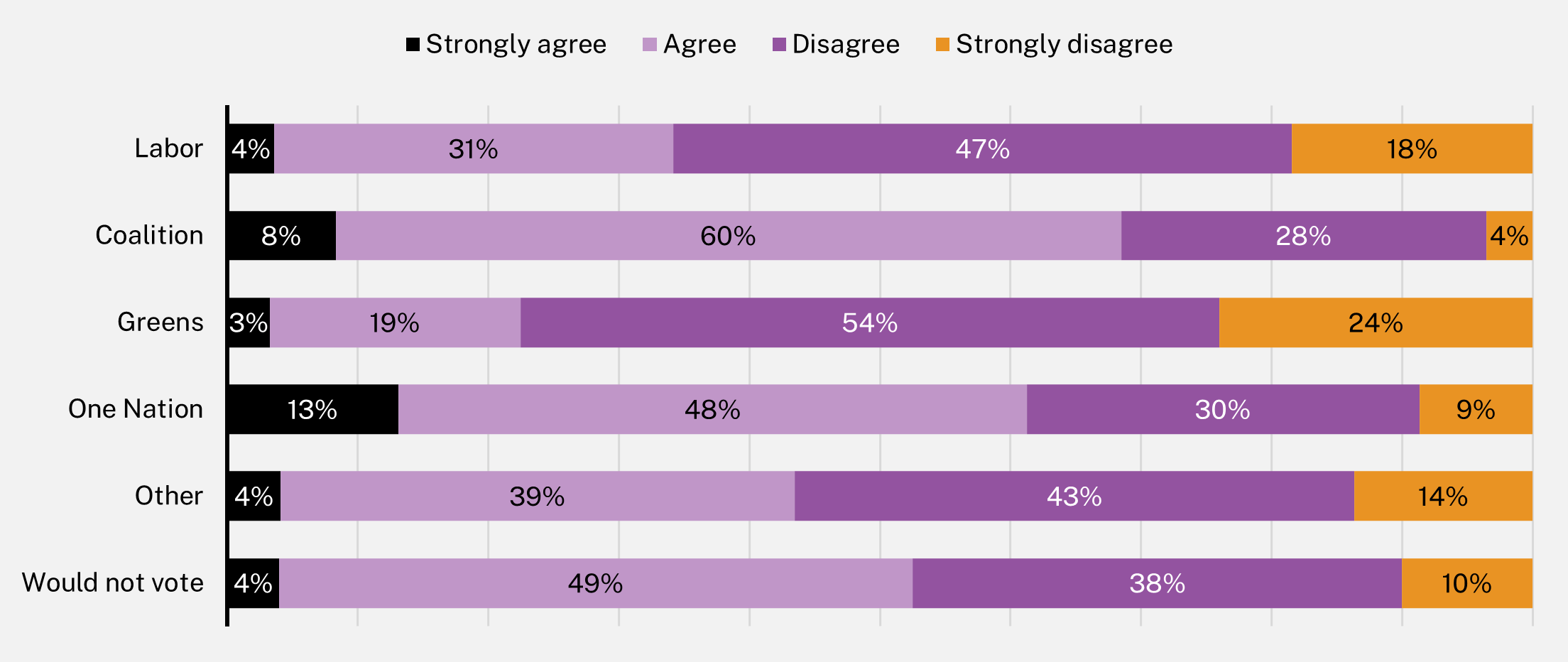

How should we interpret these results? In 2021, the strongest predictor of views on welfare adequacy in the MSC was voting intention. People who intended to vote for Coalition parties largely believed those on low incomes received enough support from the government (68% agreement), while people who intended to vote for Labor or the Greens tended to disagree with this statement (65% and 78%, respectively) (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. ‘People living on low incomes in Australia receive enough financial support from the government’, all responses, 2018–21

Figure 4. ‘People living on low incomes in Australia receive enough financial support from the government’ by participants’ voting intention, 2021

Differing political attitudes towards welfare adequacy and deservingness found in the MSC survey can be corroborated with other data.

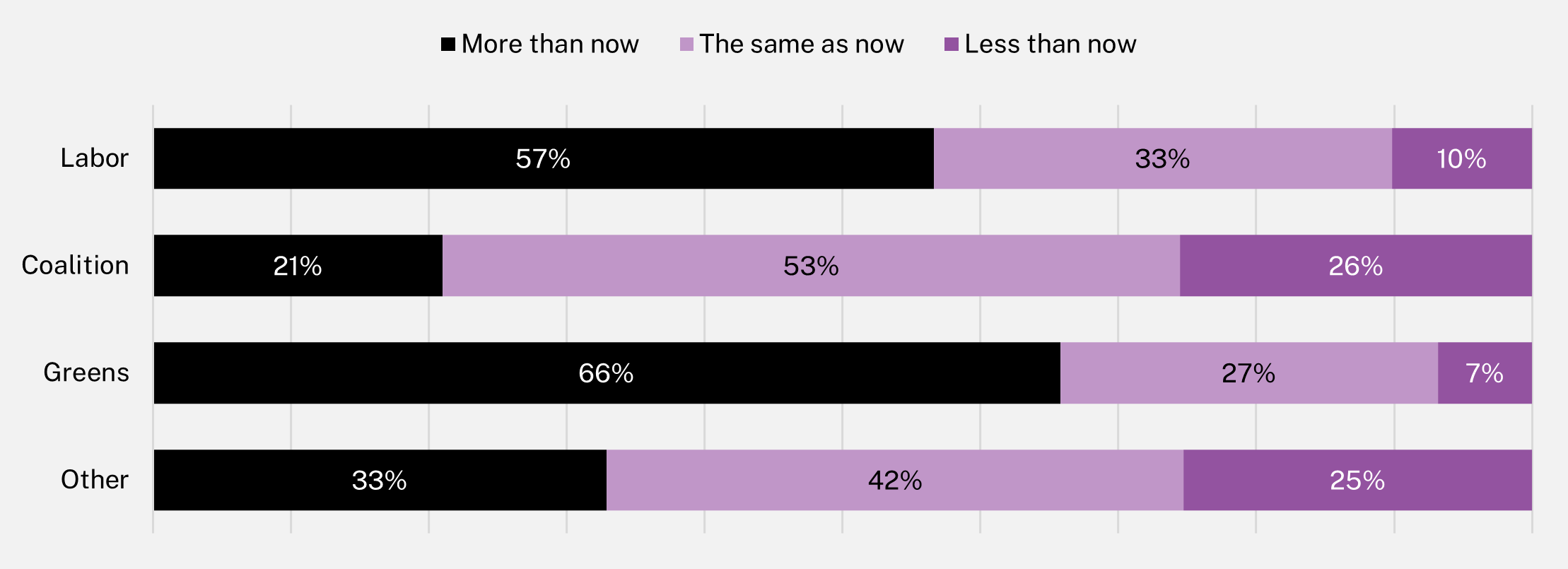

The Australian Electoral Study (AES) is a representative public opinion survey that has been conducted after every federal election since 1987.[12] Analysis of data after the last federal election in 2019 revealed a similarly significant relationship between political party affiliation and views on welfare (see Figure 5). A majority of Labor voters (57%) and Greens voters (66%) in the AES believed that government expenditure on unemployment benefits should be higher. In contrast, only 21% of Coalition voters held this view, while 53% of Coalition voters believed expenditure on unemployment benefits should have stayed at about the same levels.

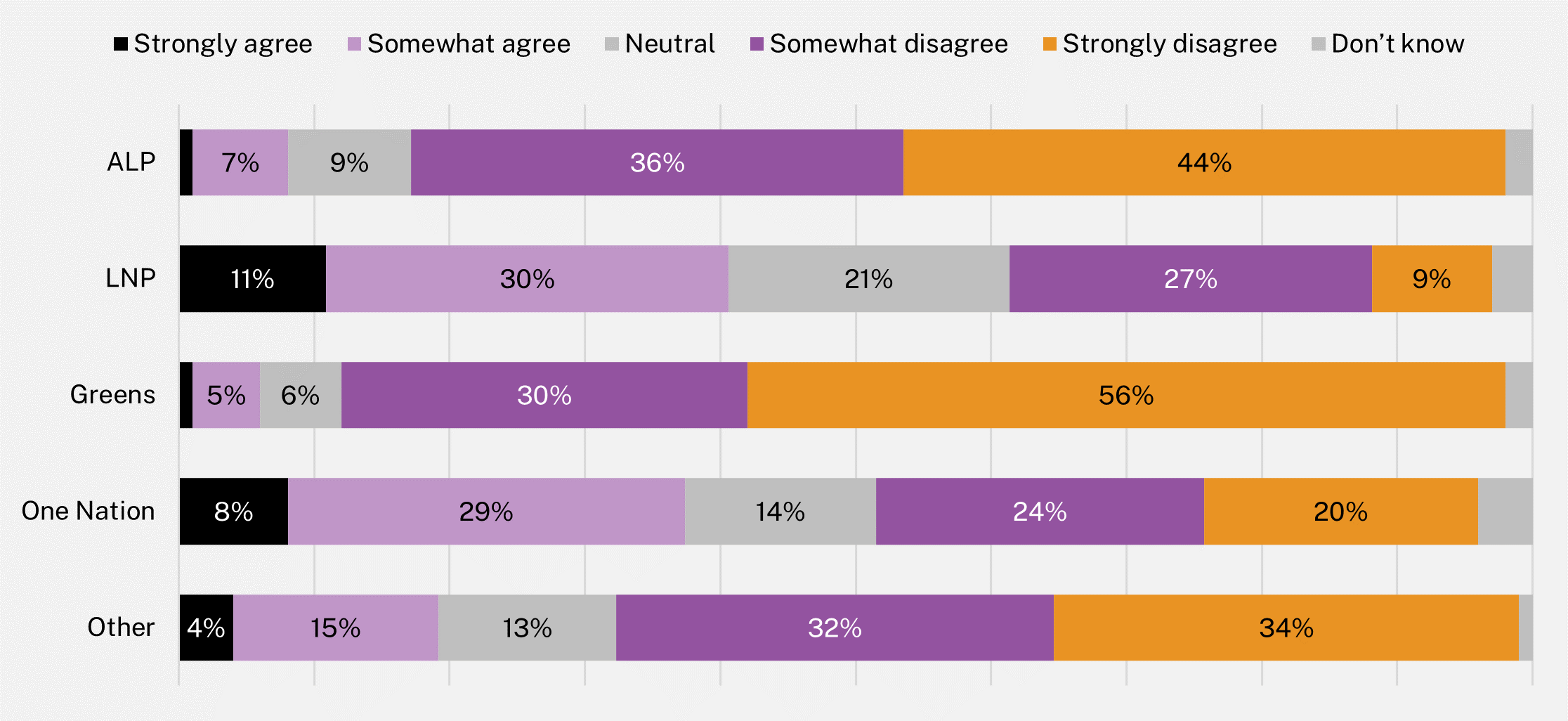

The 2019 Australia Talks National Survey, administered by the ABC and Vox Pop Labs, showed similar views amongst the Australian public. Over 21,000 people responded to the statement, ‘Poorer Australians already get enough help from the government.'[13] A strong majority of Labor (80%) and Greens (86%) voters disagreed with this statement during an election year, while only a minority (36%) of Coalition voters disagreed (see Figure 6).

Figure 5. ‘Should there be more or less public expenditure on unemployment benefits?’, 2019 (AES)

Figure 6. ‘Poorer Australians already get enough help from the government’, 2019 (Australia Talks)

Will welfare be an important issue for voters in this election?

The MSC study shows that Australians’ perceptions of social inclusion and justice issues have started falling to pre-COVID levels. The extraordinary experiences of the pandemic drove a brief collective ‘spike’ in positive views of the federal government and the temporary income support measures introduced in 2020. However, by 2021 it was clear that views on social inclusion and justice—particularly the adequacy of government income support—were once again divided.

People intending to vote for the major parties have differing opinions on whether the government is doing enough to help people. Australians who support the Coalition broadly believe current levels of welfare are adequate, while those intending to vote for Labor or the Greens tend to disagree. The evidence presented in this paper shows that these patterns largely have not changed since the last federal election in 2019.

What has changed, however, is that millions more Australians now have direct experience with the welfare system and increased financial uncertainty throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Australian researchers have previously argued that people with personal exposure to the welfare system and periods of life instability are more likely to show support for the welfare system as a social safety net.[14] Given the importance of government support for the wellbeing of so many Australians during the pandemic, perceptions of fairness and the adequacy of payments could prove be a much more important election issue for voters in 2022.

Download PDF version here.

References

[1] Andrew Markus, ‘Mapping Social Cohesion: The Scanlon Foundation Surveys, 2020’ (Scanlon Foundation Research Institute, 2021).

[2] Alex Mitchell, ‘Government COVID Handling Support Plummets’, Canberra Times, 30 November 2021.

[3] Andrew Markus, ‘Mapping Social Cohesion 2021’ (Scanlon Foundation Research Institute, 2021).

[4] Ibid., 132.

[5] Timothy P. Schofield and Peter Butterworth, ‘Patterns of Welfare Attitudes in the Australian Population’, PLoS ONE 10, no. 11 (10 November 2015).

[6] AIHW, ‘Australia’s Welfare: 2021 Data Insights’, Australia’s Welfare (Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021).

[7] AIHW, ‘Income and Income Support’, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 16 September 2021, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/income-support.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Wim Van Oorschot, ‘Who Should Get What, and Why? On Deservingness Criteria and the Conditionality of Solidarity among the Public’, Policy & Politics 28, no. 1 (January 2000): 33–48; Clara Sandelind, ‘Can the Welfare State Justify Restrictive Asylum Policies? A Critical Approach’, Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 22, no. 2 (1 April 2019): 331–46.

[10] Christian Albrekt Larsen, ‘The Institutional Logic of Welfare Attitudes: How Welfare Regimes Influence Public Support’, Comparative Political Studies 41, no. 2 (1 February 2008): 145–68.

[11] Katharine Murphy, ‘The Meaning of Morrison’s Mantra about Getting a Fair Go Is Clear. It’s Conditional’, The Guardian, 16 April 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/apr/17/the-meaning-of-morrisons-mantra-about-getting-a-fair-go-is-clear-its-conditional.

[12] Ian McAllister et al., ‘Australian Election Study, 2019’, Australian Election Study, 2019, https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.26193/KMAMMW.

[13] ABC News, ‘Australia Talks Data Explorer 2019’, ABC News, 9 December 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-10/australia-talks-data-explorer-2019/12946988.

[14] Schofield and Butterworth, ‘Patterns of Welfare Attitudes in the Australian Population’.