Administered each year since 2007, the Scanlon Foundation survey is a unique source of knowledge about how Australians view social cohesion issues. It uses a systematic methodology with large samples that provide a strong basis for analysis of sub-groups. The Social Cohesion Insights series digs deeper on the findings of recent surveys, providing added context, explanation and commentary.

Assessing our ‘political health’

The Washington DC-based Brookings Institution has described Australia as a robust and resilient liberal democracy.[1] However, a caveat in such commentary and a common refrain in the Australian media is that citizens are becoming disinterested, disillusioned or ‘disaffected’ with the Australian political system.[2] It has also been argued that some communities feel excluded from the decision-making processes that affect their daily lives.[3]

Do voters feel, as one 2022 Australian Federal Election post-mortem argued, that they are being ‘taken for granted’ by federal politicians?[4]

Counter to the notion that Australians are becoming more disillusioned, the 2021 Mapping Social Cohesion report noted that, in the context of the Scanlon surveys, Australians’ levels of trust in the federal government had reached historically high levels during the COVID–19 pandemic.[5] Nearly half (44%) of all respondents to the survey in 2021 believed that the government in Canberra could be trusted to ‘do the right thing’ most of the time or ‘almost always’. In previous years, this proportion had rarely been higher than 30%.

Of relevance for the 2022 election result is the longer-term finding that variations in measures of trust in government have corresponded with the electoral standing of the political party in power. As the popularity of the Rudd Labor Government began to decline from 2009 onwards, for instance, the MSC survey recorded an almost identical proportional decrease in levels of trust in the federal government.[6] In other words, the public’s trust correlates with satisfaction with the government of the day.[7]

Beyond public opinion about the government’s performance, a body of research has established ‘political interest, participation and the ‘civic competence’ of individual citizens’ as important indicators of liberal democracy.[8] This means that, in a robust democratic environment, people feel empowered to not only freely vote for political representatives, but to take other forms of action to advance their interests.

As the Scanlon Institute’s recent essay authored by Trish Prentice, From Petitions to Preselection, argued, ‘for democratic countries like Australia, whether and how people participate politically has an impact on the country’s political health.’[9] Australians have varying levels of knowledge, interest and barriers to engagement with politics; this edition of Insights asks what motivates their political action beyond voting in an election, and what forms this action takes.

Taking political action

Since 2007, the MSC survey has asked respondents to indicate if, in the last three years, they had taken some form of political action—including signing a petition, writing or speaking to a Member of Parliament, joining a boycott, attending a protest or demonstration, or ‘getting together with others’ to solve a local problem. In the July 2021 survey, a further option—posting or sharing political content online—was added.

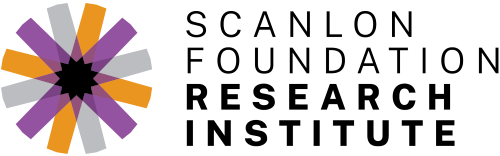

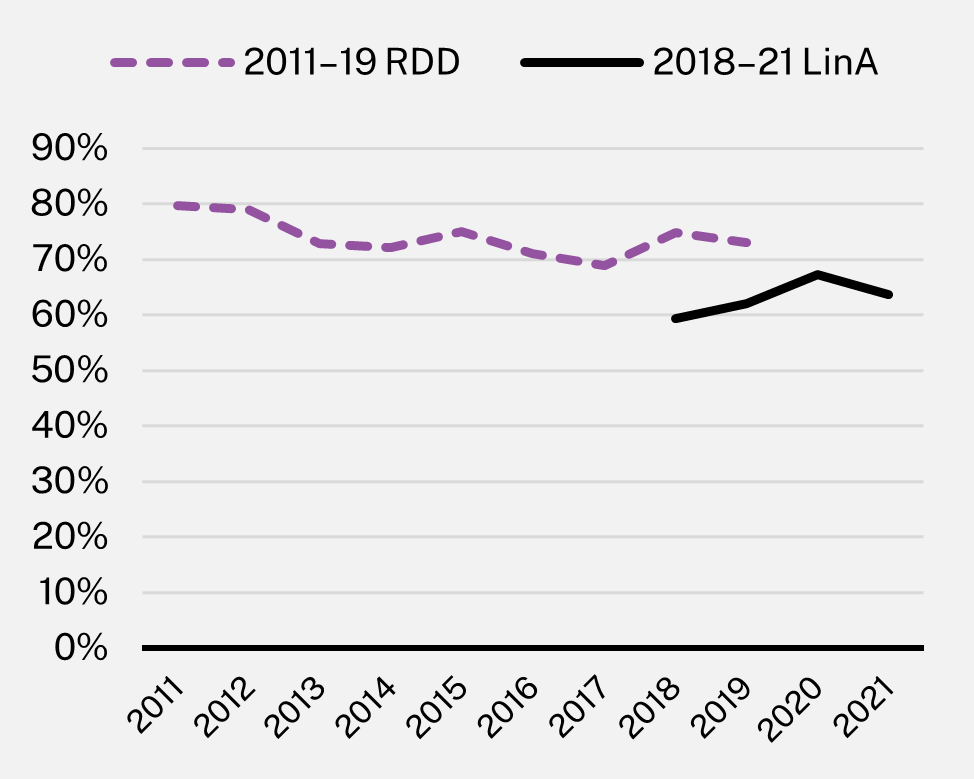

The proportion of respondents who took at least one of these forms of action was 64% in 2007 and 62% in the most recent survey, and has remained in the range 55–67%. This suggests no clear downward trend that would indicate disengagement (see Figure 1).[10]

Figure 1. Respondents who had taken some form of political action in last three years (%), 2007–21

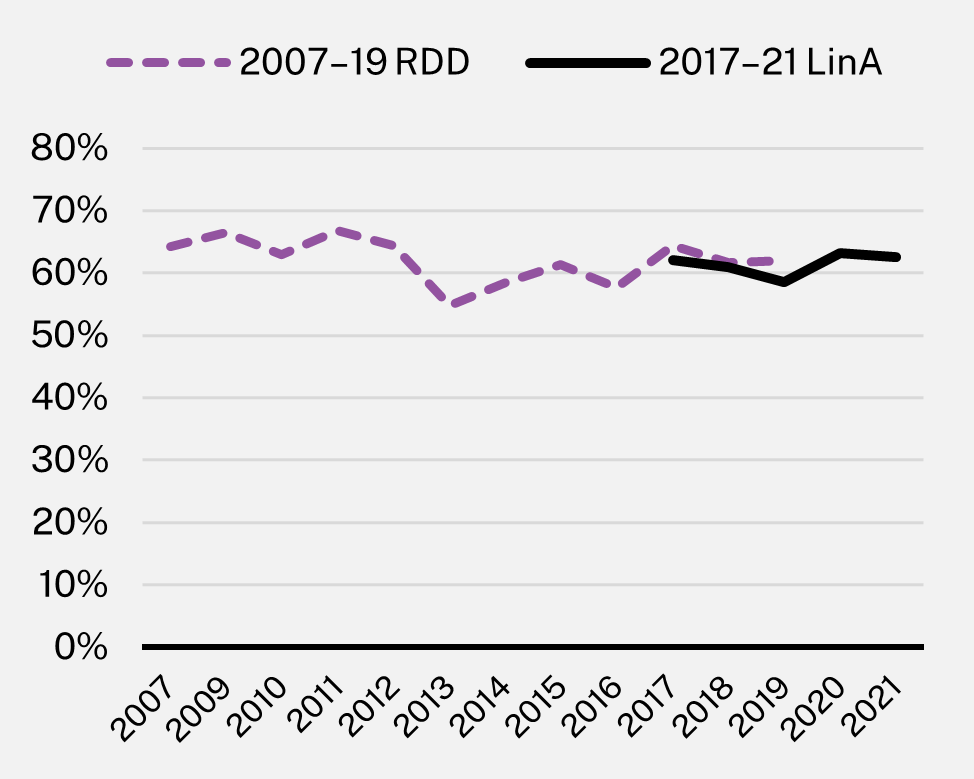

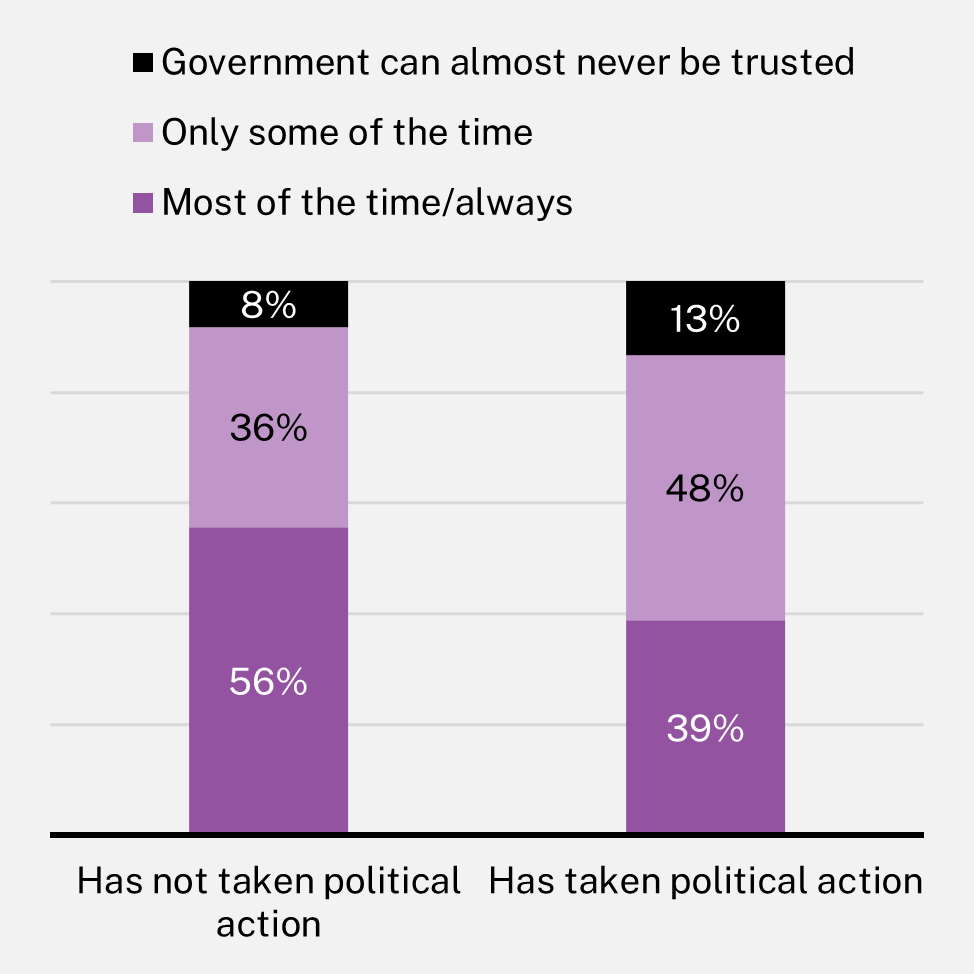

People who do take political action may be motivated by their negative appraisal of political leaders. In 2021, people who had taken some form of political action beyond voting were more likely to believe that the government could not be trusted, and that government leaders abused their power, compared to those who had not taken action (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. ‘How often do you think the government in Canberra can be trusted to do the right thing for the Australian people?’, by political action, 2021

Figure 3. ‘How often do you think government leaders in Australia abuse their power?’, by political action, 2021

Local politics may also be an arena where Australians believe they can affect change. In a section of the MSC survey that asks about the local area (‘within 15 to 20 minutes walking distance of where you live’), respondents are asked to indicate if they agree with the statement ‘I am able to have a real say on issues that are important to me in my local area.’ In 2021, nearly two-thirds (64%) of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. Since the MSC survey moved to a self-completion panel methodology in 2017, the proportion of people who agreed that they could have a real say on local issues has remained in the narrow range of 59–64% (see Figure 4).[11]

Figure 4. ‘I am able to have a real say on issues that are important to me in my local area’ (‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’), 2011–21

Distrust in federal politics may also have an impact on individuals’ engagement with local politics. In 2021, amongst those who thought the federal government could ‘almost never’ be trusted to do the right thing by the Australian people, more than half (54%) also disagreed that they were able to have a real say on local issues that were important to them.

Getting involved locally

For the first time, in 2021 the MSC survey asked respondents to indicate whether in the past 12 months they had been actively involved with community support groups (such as charities or volunteer associations), social or religious groups (such as sports clubs or churches), or civil or political groups (such as trade unions or political parties).

In 2021, more than half (54%) of Australians had been actively involved in at least one of these groups. People who believed they could have a real say on local issues had slightly higher rates of active involvement (57%).

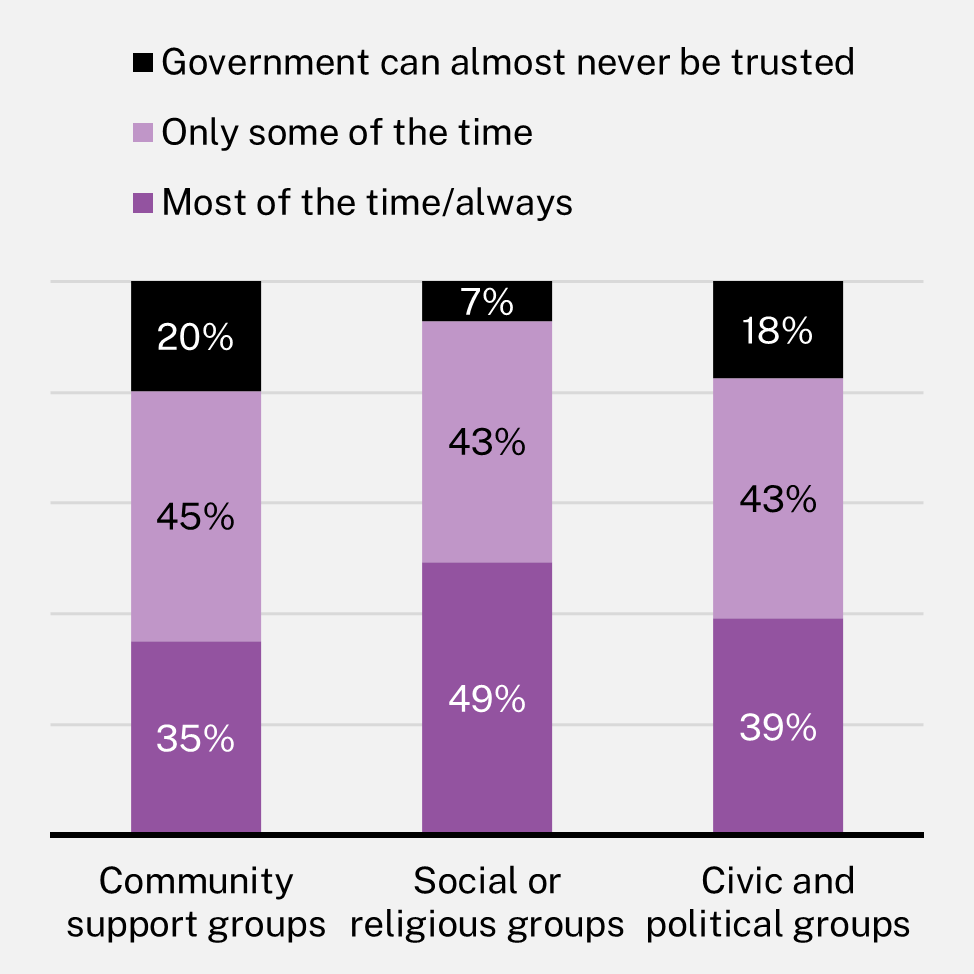

The survey demonstrated a relationship between low levels of trust in the federal government and active participation in community groups. People who were involved with groups such as Rotary Clubs, charities or volunteer emergency services had lower levels of trust in government, as did those who were involved in trade unions, political parties, or rights and advocacy groups (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. ‘How often do you think the government in Canberra can be trusted to do the right thing for the Australian people?’, by involvement in groups, 2021

Migrant communities

It is sometimes argued that migrants—particularly those from non-English speaking backgrounds—do not see themselves reflected in Australia’s political leadership.[12] In the last Federal Parliament, for instance, only 12 out of 76 Senators and 13 out of 151 Members of the House of Representatives were born overseas.[13] Even fewer were born in countries where English is not the main language spoken.

The Petitions to Preselection essay highlighted that migrants and people from non-English speaking backgrounds engage in diverse forms of political action. Many of the individuals who shared their stories said that they had felt somewhat excluded from Australian political life, whether due to language barriers, lack of shared knowledge in their communities about Australian politics, or feelings of being ignored by politicians. For instance, Joannie, an activist for the organisation Democracy in Colour, said:

“When we don’t get listened to or we don’t get heard by the people who are supposed to listen to us, it feels very disheartening.”

Perhaps encouragingly, the MSC survey showed that people born overseas had high levels of trust in the federal government: 91% believed that the government could be trusted at least some of the time, compared to 87% of Australian-born respondents.

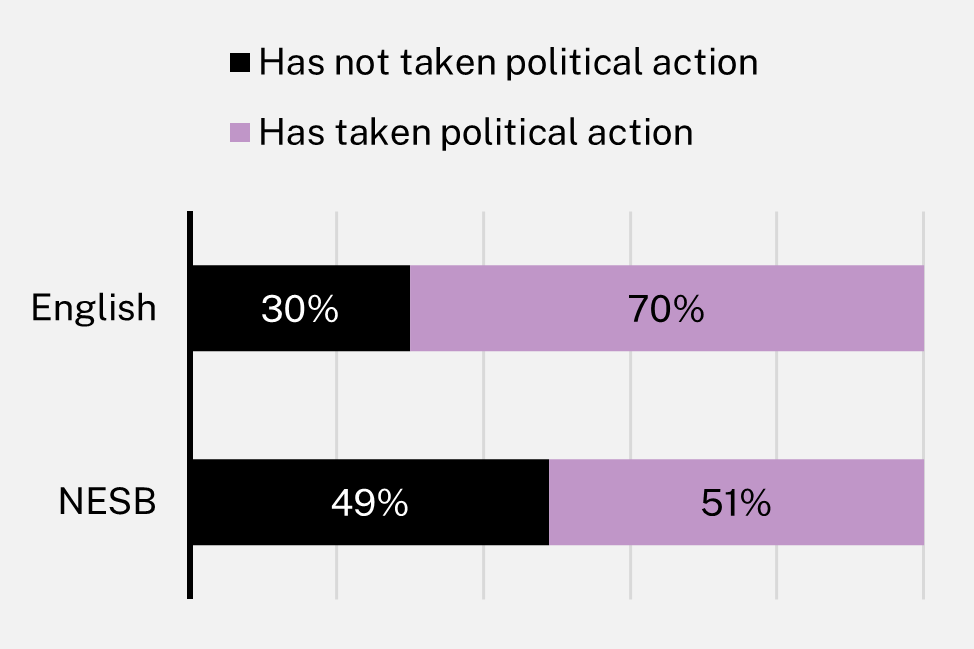

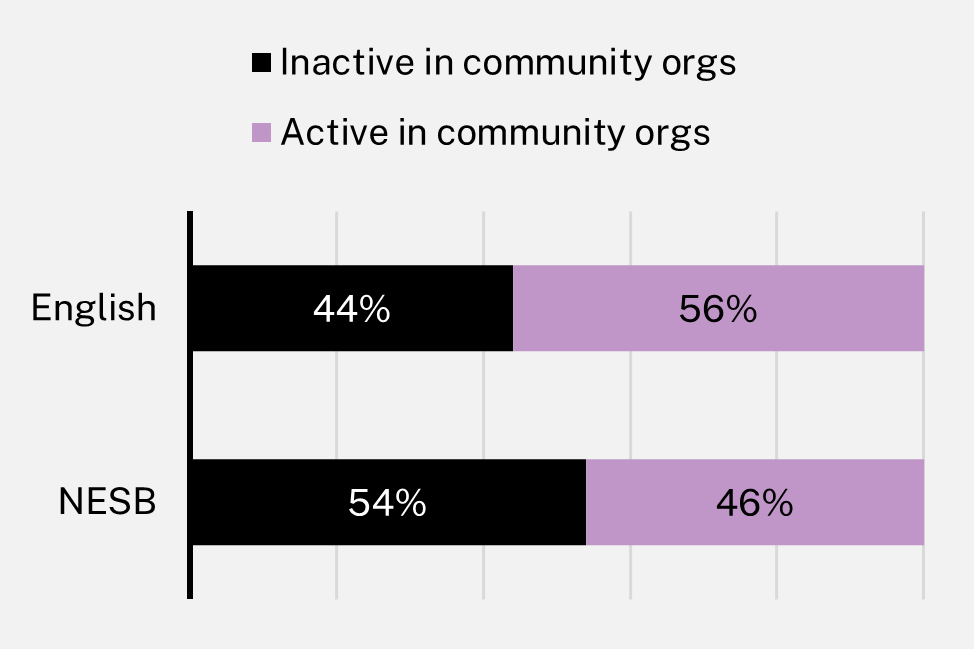

However, the MSC survey results look somewhat different when we examine migrants’ political action and community group involvement. People from non-English speaking backgrounds (NESB) had much lower rates of political action (aside from voting in elections) when compared to native English speakers (see Figure 6). People from non-English speaking backgrounds also had lower rates of active participation in community organisations compared to people with English as their first language (see Figure 7).

These findings reflect some of the views that were voiced in the Petitions to Preselection essay. For instance, Tu Le, a former candidate for the NSW Federal seat of Fowler, said:

“There is a sense, in migrant communities, that Australia is not necessarily our home. We are still guests in this country, so maybe we don’t have a right to have a say or we don’t have a right to be as politically engaged.”

Nevertheless, the essay demonstrates how migrant community leaders had formed their own political advocacy organisations, been appointed as councillors in local government, ran for election, and worked on increasing awareness about politics amongst their communities.

Figure 6. Respondents who had taken some form of political action in last three years, by language group, 2021

Figure 7. Active involvement in community organisations, by first language group, 2021

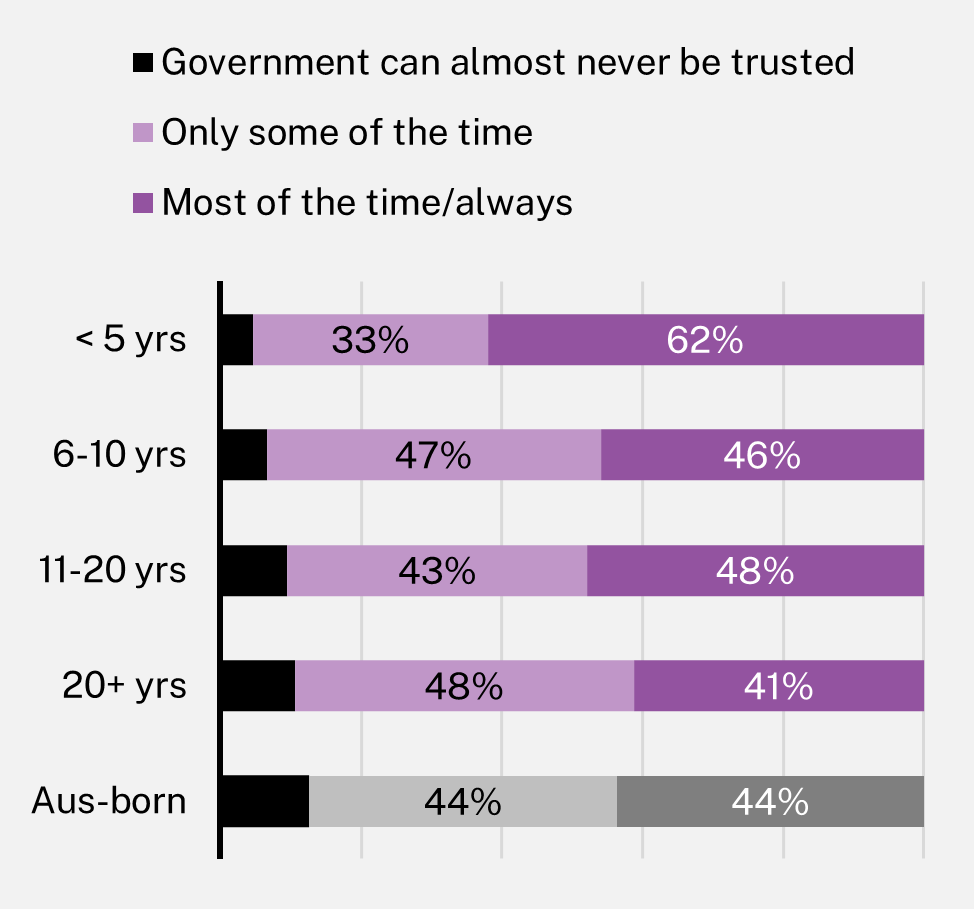

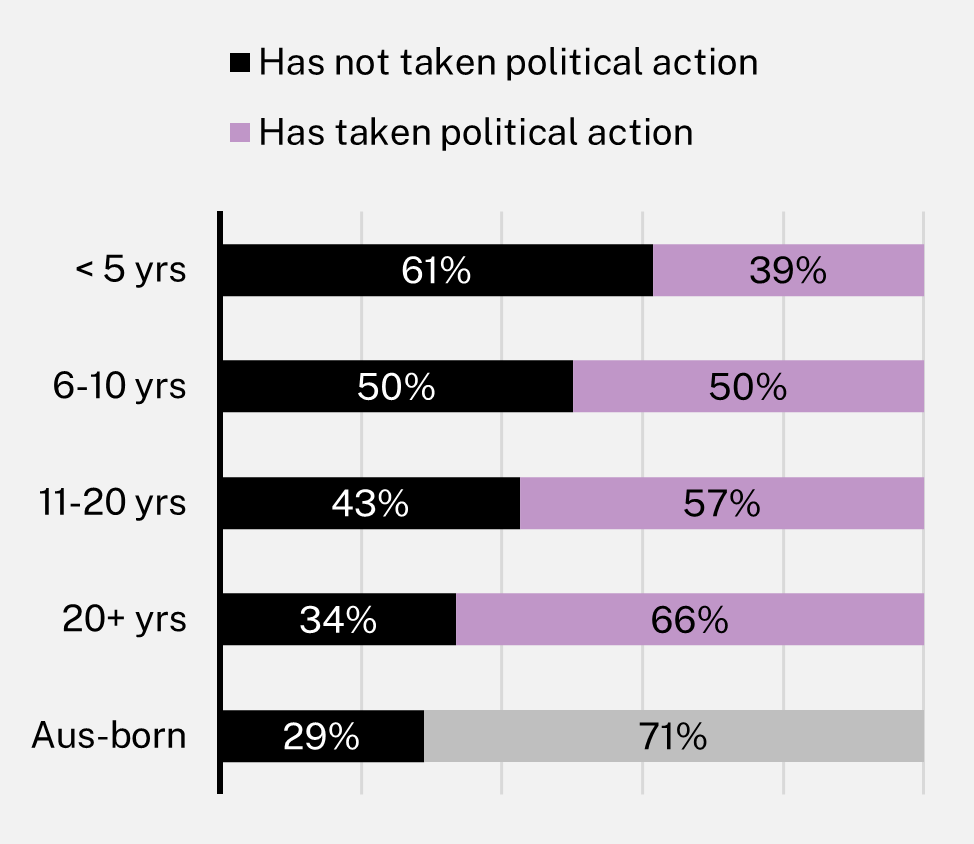

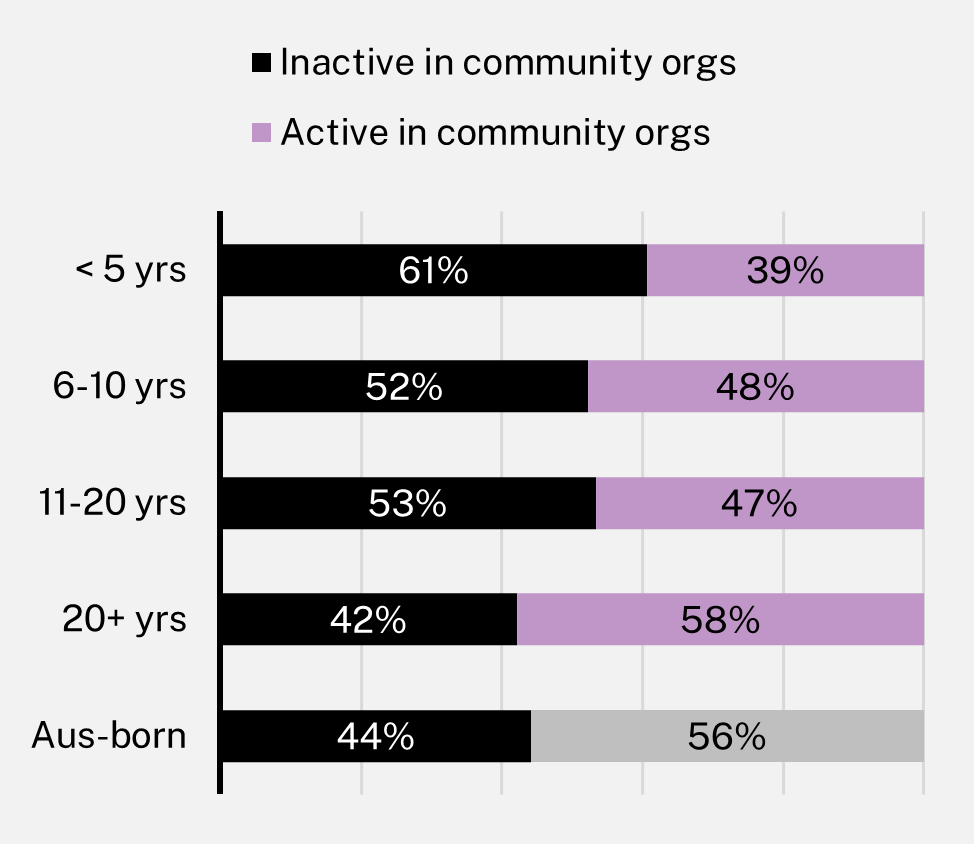

An important aspect of political engagement for migrant communities is their citizenship status and duration of residence in Australia. The 2021 MSC survey data demonstrates that people who arrived in Australia more than 20 years ago had lower levels of trust in the federal government, and higher rates of both political action and involvement in community organisations, compared to recent arrivals (see Figures 8–10).

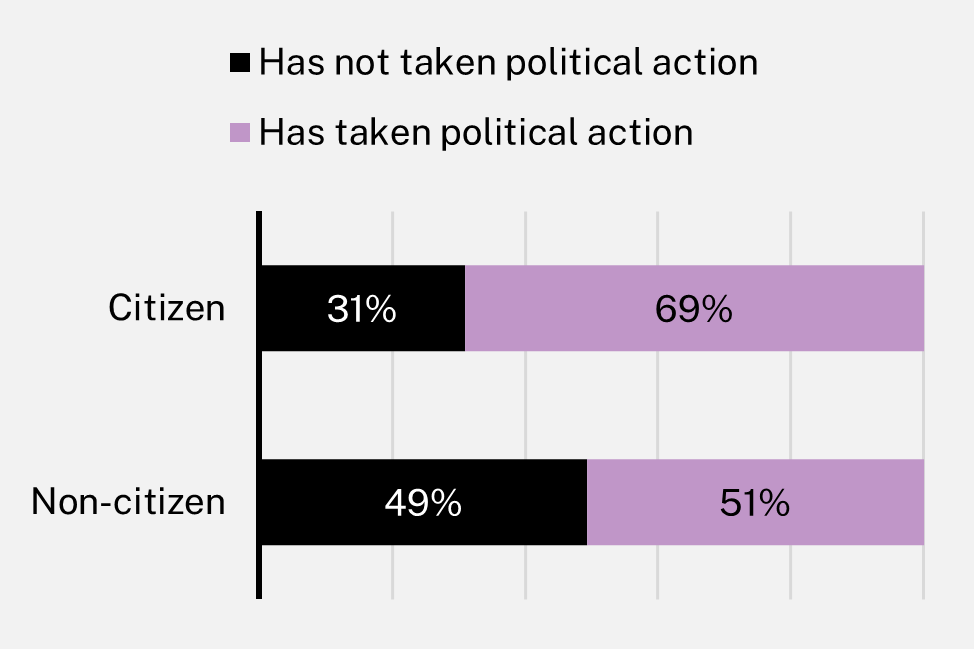

More recent arrivals to Australia (those who had migrated fewer than five years ago) demonstrated high levels of trust in the government, along with low levels of political action and community group engagement. Political action was also much higher amongst Australian citizens than non-citizens (see Figure 11).

Figure 8. ‘How often do you think the government in Canberra can be trusted to do the right thing for the Australian people?’, by duration of residence in Australia, 2021

Figure 9. Recent history of political action, by duration of residence in Australia, 2021

Figure 10. Active involvement in community organisations, by duration of residence in Australia, 2021

Figure 11. Respondents who had taken some form of political action in last three years, by citizenship status, 2021

Conclusions

The MSC survey shows that, far from being ‘disaffected’ or disengaged in politics, Australians have maintained steady rates of political action (outside of voting) since 2007. Lower levels of trust in the federal government and suspicion that political leaders were abusing their power was associated with her rates of political action—particularly signing petitions and sharing political content online.[14]

There may also be some truth to the adage that ‘all politics is local.’ Survey respondents who did not trust the government to ‘do the right thing’ took action by joining local community support groups or civic and political groups. In general, having a say on local issues of importance appears to be a realistic proposition for a majority of the population.

Recent arrivals to Australia and migrants from non-English speaking backgrounds, however, had demonstrably lower levels of political engagement in 2021 than longer-term residents, citizens and those born in Australia. The stories featured in the Petitions to Preselection essay also suggest that there is frustration within some migrant communities that they are not being listened to in the political process. It will be important for future research and community engagement to consider how language, citizenship status and community dynamics act as barriers or enablers of political participation in Australia.

References

1. John Lee, ‘The Risks to Australia’s Democracy’, Brookings (blog), 22 January 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-risks-to-australias-democracy/.

2. Ibid.; Henry Belot, ‘Australians “Disaffected with Political Class”, Study Shows’, ABC News, 19 December 2016, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-12-20/2016-australian-election-disaffected-study/8134508.

3. Stephen Harrington, ‘Australians Couldn’t Care Less about Politics? Really?’, The Conversation, 4 February 2016, http://theconversation.com/australians-couldnt-care-less-about-politics-really-53875.

4. Annika Smethurst, ‘“All Politics Is Local”: Coalition’s Winners Reveal Secret of Success’, The Age, 27 May 2022.

5. Andrew Markus, ‘Mapping Social Cohesion 2021’ (Scanlon Foundation Research Institute, 2021).

6. Andrew Markus, ‘Trust in the Australian Political System’, Parliament of Australia, October 2014, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Powers_practice_n_procedures/pops/pop62/c03.

7. When available, the next wave of the MSC survey in 2022 will likely provide further insights into this relationship.

8. Dirk Berg-Schlosser, ed., Democratization: The State of the Art, 2nd ed. (Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2007).

9. Trish Prentice, ‘From Petitions to Preselection: Stories of Political Participation from Culturally Diverse Australians’, Essay (Scanlon Foundation Research Institute, 2022), https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Powers_practice_n_procedures/pops/pop62/c03.

10. MSC surveys conducted between 2007–19 were administered to landline and mobile phone numbers, employing Random Digital Dialling (RDD). Between 2017–19 the survey was administered in parallel by RDD and on the Social Research Centre’s Life In AustraliaTM (LinA) panel, to provide understanding of the impact of mode of administration on survey results. Since 2019, the survey has been administered solely on the LinA panel. Differences in the typical responses of participants on the RDD and LinA panel can sometimes be explained by the willingness to provide a more truthful response when respondents self-complete a survey, as distinct from responding to an interviewer. See Markus, ‘Mapping Social Cohesion 2021’.

11. See previous note for explanation of variance according to the survey methodology.

12. Frances Mao, ‘Australia Election: Why Is Australia’s Parliament so White?’, BBC News, 20 May 2022, sec. Australia, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-61432762.

13. Parliamentary Library, ‘Parliamentary Handbook of the Commonwealth of Australia 2020’ (Canberra: Department of Parliamentary Services, 2020).

14. Markus, ‘Mapping Social Cohesion 2021’.