Starting in 2007 and administered each year since 2009, the Scanlon Foundation surveys are a unique source of data about how Australians view social cohesion issues. The surveys use a systematic methodology with large samples that provide a strong basis for analysis of sub-groups. The Social Cohesion Insights series digs deeper into the findings, and provides added context, explanation, and commentary.

Download PDF version here.

The economic benefits of immigration

As an island nation with no contiguous borders, Australia is in a rare position globally to be able to tightly manage immigration. The size and composition of the intake are directly determined by the Federal Government each year through the budget process. As the number of people wanting to come to Australia exceeds available places, program targets are usually fulfilled precisely.

With a focus on skilled migrants—who normally make up between one-half to two-thirds of all permanent places[1]—governments of both major political parties have used immigration as a tool to ‘promote economic prosperity and fiscal sustainability.'[2] Immigration is thought to increase the labour force participation rate and real GDP per person, as well as improving the government’s budget bottom line.[3]

In 2021, Treasury projected that the lifetime fiscal impact of a skilled migrant on the Government budget was $319,000, compared to a negative fiscal impact of –$104,000 for the ‘general population’.[4] This is because skilled migrants are, on average, younger than the rest of the population, and contribute more through taxes than they draw down in government services over their lifetime.[5]

Modelling by the Migration Council of Australia has shown that a skills-focused migration program, by increasing competition mainly at the higher end of the labour market, creates additional demand and subsequent wage increases amongst medium and lower-skilled workers—the largest share of the Australian workforce.[6] According to the MCA, these wage adjustments mitigate any impacts of migration on unemployment.[7] This finding aligns with evidence from other countries, where researchers have found negligible (if any) effects of immigration on welfare, wages, and employment for local workers.[8]

Nevertheless, immigration remains one of the most politically charged areas of public policy in Australia. Particularly in uncertain economic times—when people feel that their jobs or status may be under threat—immigrants are seen by some as a source of competition for scarce resources.[9] This edition of Social Cohesion Insights examines Australians’ views about immigration as the country enters a period of economic uncertainty and ‘probable’ recession.[10]

Public opinion

Despite the evidence demonstrating the economic benefits of migration, public opinion does not always support it. In Australia, migrants of almost all entry pathways, skills profiles, and cultural backgrounds have been blamed—particularly by right-wing political parties—when economic conditions get tough.[11] The public perception of immigration has also been affected by exposure to negative messages in political discourse and the media, including the use of sensationalist terms like ‘floods’ or ‘invasions.’[12]

Economic and political conditions

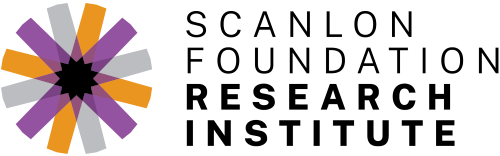

Since 2007, the Scanlon Foundation surveys have asked participants: ‘What do you think about the number of immigrants accepted into Australia in recent years? Would you say it has been… (1) too high, (2) about right, (3) too low?’

In an analysis of earlier findings using this question, Professor Andrew Markus argued:

In a period of increasing or relatively high unemployment, there is majority support for the view that the intake is too high; in times of economic growth and relatively low unemployment, the majority supports the current intake or its increase. Four of the five Scanlon Foundation surveys conducted between 2007 and 2012, a time of relatively low unemployment, found that 53–56% of respondents considered that the intake was ‘about right’ or ‘too low’. In 2010 there was a statistically significant fall, to 46%, in the context of economic concerns and politically divisive debate over population growth.[13]

Indeed, 2010 was one of the few waves of the Scanlon surveys when a slim majority of respondents believed the immigration intake was too high (see Figure 1). The Australian economy had at the time experienced a ‘sharp but very brief downturn’ following a global recession.[14] While business and consumer confidence fell, as did external demand and domestic spending, the negative effects were short lived—in part driven by continued strong population growth.[15]

Figure 1. Perceptions of the number of immigrants in recent years, Scanlon Foundation surveys (RDD, 2007–2019)

In 2009, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said that he supported Treasury’s demographic projections for a ‘big Australia’, including consistently high rates of immigration through to 2050. Actual immigration numbers had reached then-historically high levels of nearly 170,000 new permanent residents annually. Use of the term ‘big Australia’ triggered what Professor Markus referred to as ‘politically divisive debates’ about immigration, drawing in concerns about sustainability, infrastructure, suburban sprawl, and government health and welfare spending.[16] The impacts on the public’s views about immigration to Australia are reflected in the Scanlon survey findings.

Belief that Australia’s immigration levels were too high began to climb again after 2016, reaching 45% of all survey respondents in 2018. However, under Prime Minister Scott Morrison, permanent migration had by then fallen to 160,000 places—the lowest level in ten years.

Unlike in the post-GFC period, there was no economic downturn in Australia in 2018 that could explain rising negative sentiment towards immigration levels (though assessments of the Australian economy highlighted vulnerabilities relating to high household debt and low housing affordability).[17]

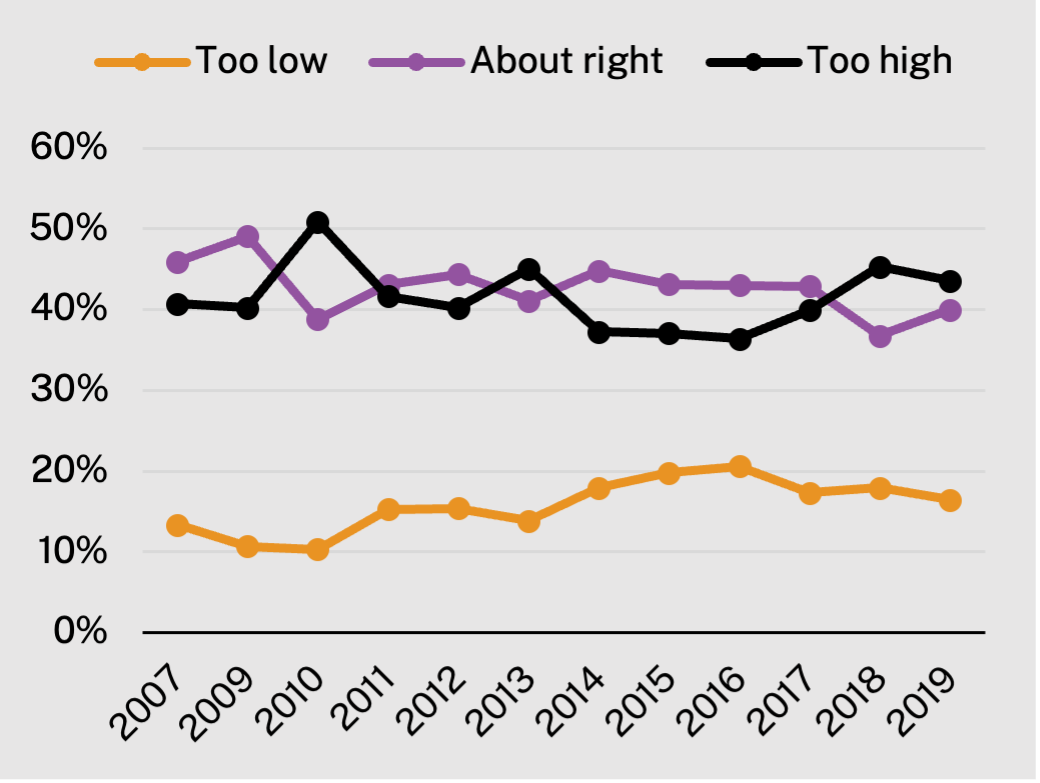

Uneasiness about immigration numbers was also reflected in other surveys from the same period. The Australian Election Study, which collects data from a nationally representative sample of voters after each election, asks participants whether they think the number of immigrants allowed into Australia ‘should be reduced or increased.’[18] Though the wording of questions differs, results show a similar pattern to the Scanlon surveys, with high levels of opposition in 2010 and after 2016 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Opposition to levels of immigration, Scanlon surveys and Australian Election Study (2007–2019)

These trends suggest the need to develop a better understanding of what influences public opinion on immigration, beyond basic macroeconomic or political trends.

Immigration and ‘social desirability’

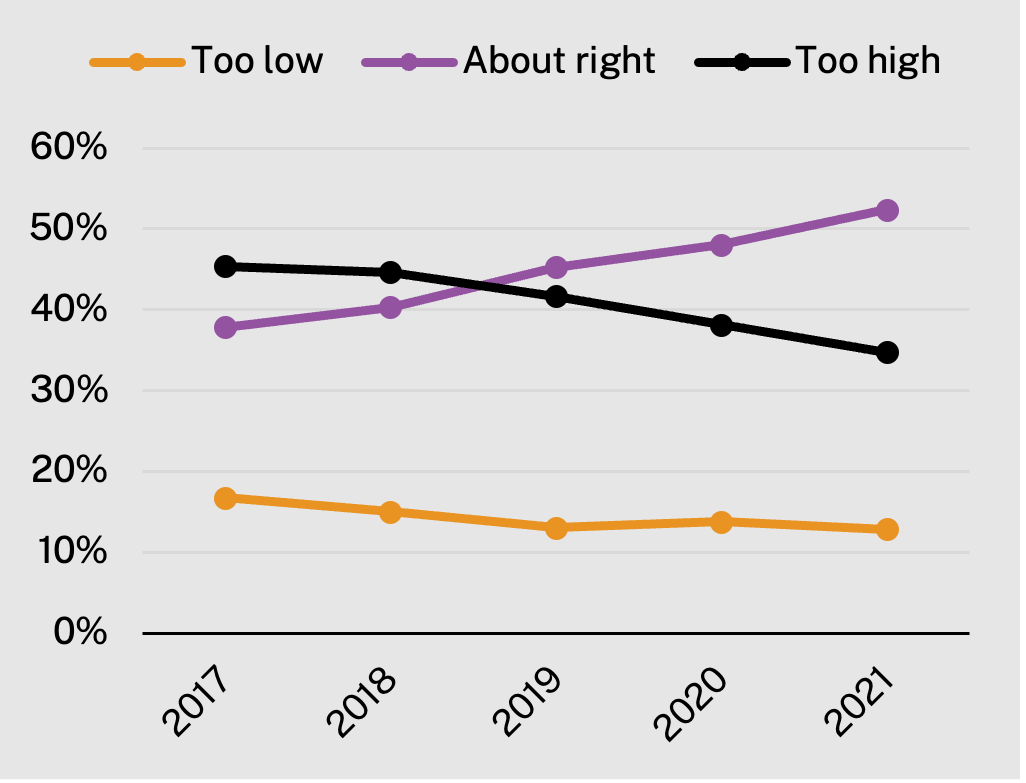

From 2017 onwards, the Scanlon surveys began collecting responses from Australia’s only probability-based panel, via a self-completed survey method. This differs from the interviewer-administered, ‘Random Digital Dialling’ (RDD) approach used in earlier waves of the survey. According to the theory of social desirability bias, the self-completion method generates more ‘truthful’ responses to survey questions than when a participant is required to provide a verbal answer to an interviewer.[19]

In the last few waves of RDD-administered surveys (2017–19),the proportion of people who thought immigration levels were ‘too high’ was in the range 40–45%. However, results from the 2017–21 waves administered on the Life in AustraliaTM panel (using the self-completion mode) show a decline in the proportion of respondents who thought immigration was ‘too high’ (see Figure 3). There was also a concurrent increase in those who though immigration levels were ‘about right’—reaching 52% in 2021.

Figure 3. Perceptions of the number of immigrants in recent years, Scanlon Foundation surveys (LinA, 2017–2021)

The theoretically more ‘truthful’ responses of the panel approach show increasing support and decreasing opposition to the levels of immigration between 2017–21. Actual increases in new permanent residents did not exceed the ‘ceiling’ of 160,000 places annually set by the Morrison Government during this time, including a significant drop in 2020–21 due to COVID–19.

Who supports current levels of immigration?

In 2018, the European Observatory of Public Attitudes to Migration (OPAM) published a multi-country analysis of European opinion polls that aimed to explain why attitudes to migration ‘are what they are’.[20]

The authors argued that the strongest and most stable predictors of attitudes to immigration were deeply held values and ‘moral foundations,’ as well as education, lifestyle, and political attitudes. A range of other ‘weak and unstable’ effects included contact with other ethnic groups, neighbourhood crime, media influence and perceived economic competition.

Findings at the individual level of the OPAM study were that:

…younger respondents, women, those with a university degree, those who live in an urban area, who have trust in their country’s institutions, who are generally trusting of others, who feel safe at dark and those who use the internet daily have significantly more positive attitudes towards immigration.[21]

When examining responses to the Scanlon surveys, there are significant sub-group differences that correspond to the findings of the OPAM study.

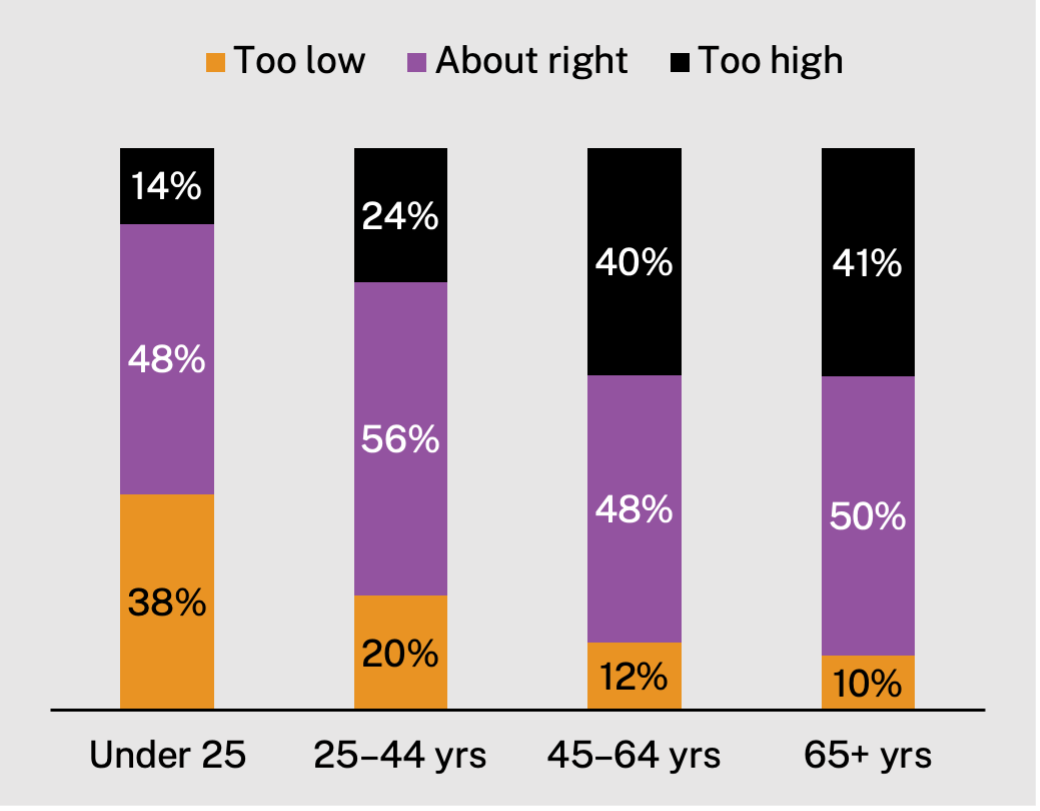

For instance, people under the age of 45 were more likely than their older counterparts to support current levels of immigration (see Figure 4). The vast majority (86%) of young people (under 25) believed immigration numbers were either too low or about right.

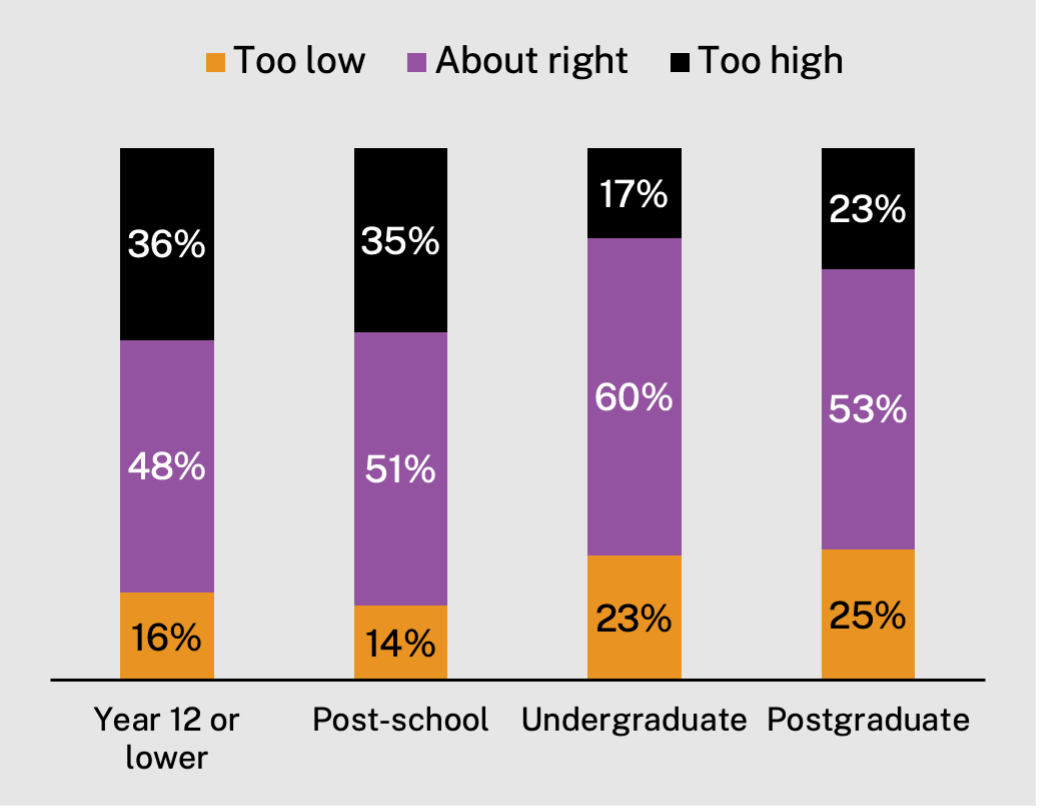

People with a university-level education also had more positive views about the number of immigrants than those who had high school, trade, apprentice, diploma, or certificate-level education (see Figure 5).

Figure 4. Perceptions of the number of immigrants accepted into Australia by age group (2021)

Figure 5. Perceptions of the number of immigrants accepted into Australia by education level (2021)

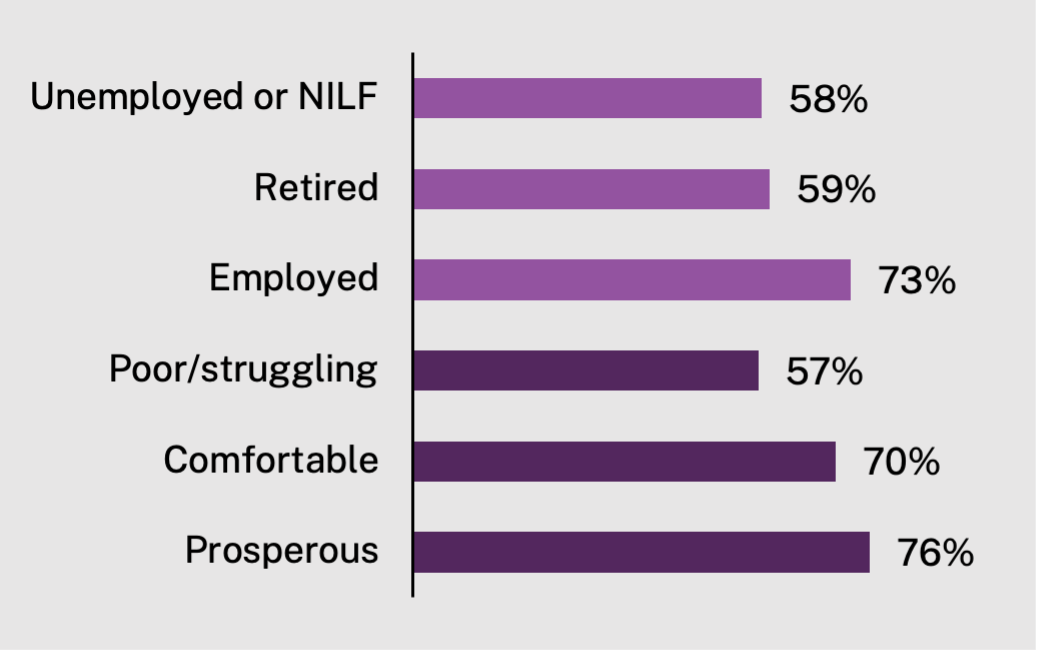

Economic security played a role in influencing support for immigration. Figure 6 shows the economic circumstances of people who believed the number of immigrants accepted into Australia was ‘about right’ or ‘too low’ (positive views). Employed persons were likely to have the highest levels of support, as were those who believed they were financially ‘comfortable’ or ‘prosperous.’

Figure 6. Perceptions of the number of immigrants accepted into Australia (positive), by economic circumstances (2021)

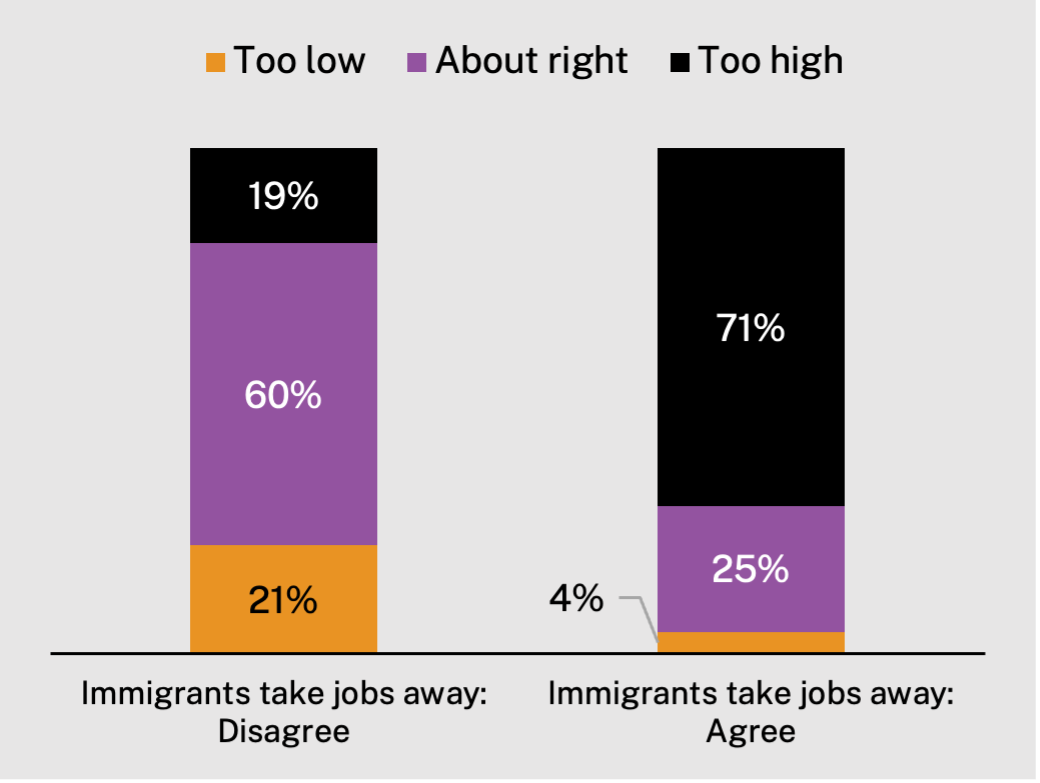

There is a similar association between support for immigration and its perceived threat to economic security. As noted, immigrants may be held responsible for job losses—even if those losses are the effect of structural disruptions such as trade policies or technological change.[22] In this way, immigrants can sometimes become a ‘convenient scapegoat’ for the social and economic anxiety felt by some members of the host community.[23]

Scanlon survey results from 2021 show that people who believed that ‘immigrants take jobs away’ (about 24% of the entire sample) were more likely to think that immigration levels were currently too high (see Figure 7). The results confirm the association between seeing immigration as an economic threat and a desire for lower levels of immigration to Australia.

Figure 7. Perceptions of number of immigrants accepted into Australia by belief that they ‘take jobs away’ (2021)

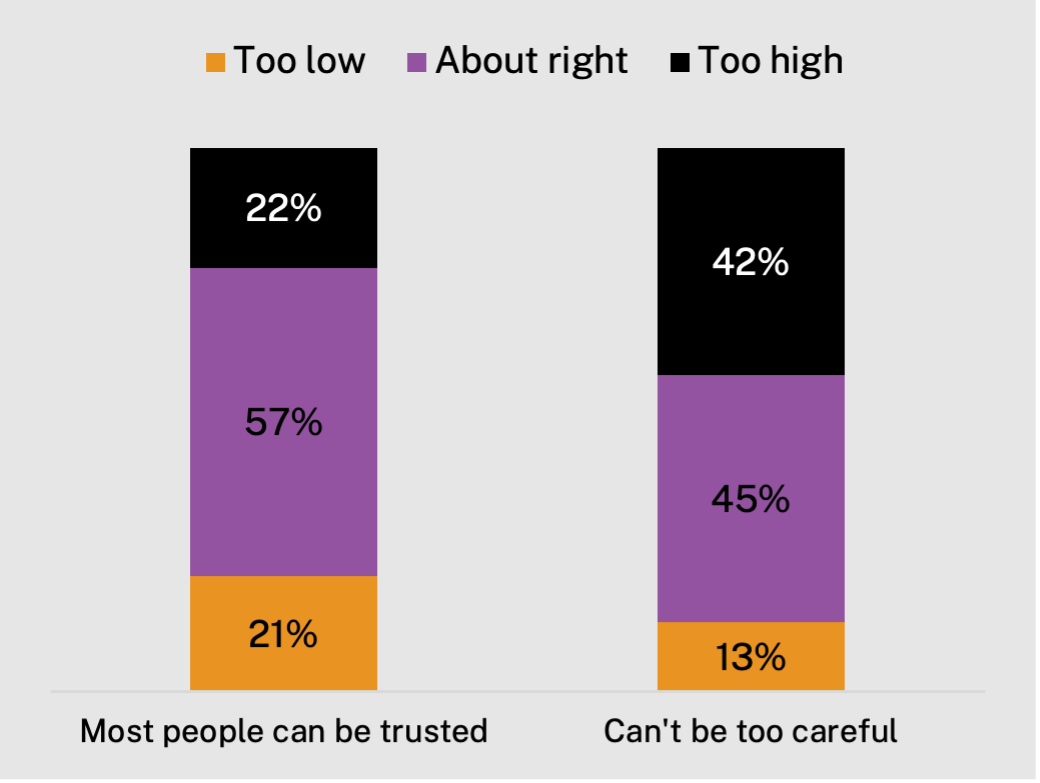

Finally, and in line with the OPAM study findings, social trust is positively correlated with support for immigration. In other words, respondents who believed that people could generally be trusted (about 52% of the entire sample) were more likely to have a positive view of the number of immigrants coming into Australia (see Figure 8). It is worth noting, as in a previous edition of Social Cohesion Insights, that high levels of generalised social trust are also associated with greater financial security.[24]

Figure 8. Perceptions of the number of immigrants accepted into Australia by levels of social trust (2021)

Discussion

The 2021 Scanlon surveys showed that almost two-thirds (65%) of Australians thought the number of immigrants in recent years was either ‘about right’ or ‘too low.’ As the current Government prepares to restore the immigration intake to record pre-COVID levels, it remains to be seen whether this relatively high public support will continue.

Individuals who are more concerned about levels of immigration are likely to be older, in situations of financial insecurity, or have lower levels of trust in other people generally. This aligns with findings from studies of attitudes towards immigration in other parts of the world.

Historical data shows that concerns about immigration levels can ‘spike’ during periods of economic instability—and the Treasurer has warned that there are tough times ahead for Australia.[25] But will this minority opinion matter in the contemporary Australian context?

Recent research suggests that we should pay attention to how negative attitudes towards immigration drive political engagement through voting and activity on social media.[26] Hence, someone who is concerned about high levels of immigration is likely to be more incentivised to support politicians who oppose a ‘big Australia.’

Indeed, the Scanlon Foundation surveys show that in 2021, 67% of One Nation voters thought that immigration was too high, compared to 39% of LNP voters, 22% for Labor, and 13% for the Greens. In the last pre-COVID survey (2019), immigration ranked as ‘the most important problem facing Australia today’ amongst One Nation voters; for LNP supporters it was second, with Labor and Greens voters ranking immigration as a much less important issue.

While governments often argue that skills-based immigration brings ‘prosperity and sustainability,’ there are engaged voters who strongly disbelieve this claim. As immigration increases again during a time of economic uncertainty, there is a need to maintain a focus on fostering social inclusion, trust, and the cohesiveness of Australian society.

Back to topReferences

1. Department of Home Affairs, ‘2020–21 Migration Program Report’ (Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs, 2021).

2. Productivity Commission, ‘Migrant Intake into Australia’, Inquiry Report (Canberra: Productivity Commission, Australian Government, 13 April 2016).

3. Migration Council of Australia, ‘The Economic Impact of Migration’ (Migration Council Australia and Independent Economics, 2015).

4. Treasury, ‘2021 Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 Years’ (Commonwealth of Australia, June 2021).

5. Migration Council of Australia, ‘The Economic Impact of Migration’.

6. Over 60% of Australian workers are employed in occupations classified at skills level 3–5 (medium and low levels) of the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO). Approximately 39% are employed as managers or ‘professionals’ (the highest skill levels). National Skills Commission, ‘All Regions (ABS SA4) Downloads’, Labour Market Insights, 2022, https://labourmarketinsights.gov.au/regions/data-downloads/all-regions-abs-sa4-downloads/#8..

7. Migration Council of Australia, ‘The Economic Impact of Migration’.

8. See for example Thomas K. Bauer, Regina Flake, and Mathias G. Sinning, ‘Labor Market Effects of Immigration: Evidence from Neighborhood Data’, Review of International Economics 21, no. 2 (2013): 370–85; Cynthia Bansak, Nicole Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny,

9. Chan-Hoong Leong, ‘A Multilevel Research Framework for the Analyses of Attitudes toward Immigrants’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Convergence of Cross-cultural and Intercultural Research, 32, no. 2 (1 March 2008): 115–29.

10. Gareth Hutchens, ‘Is Australia Headed for a Recession?’, ABC News, 24 September 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-24/is-australia-headed-for-a-recession/101467854.

11. Jackie Hogan and Kristin Haltinner, ‘Floods, Invaders, and Parasites: Immigration Threat Narratives and Right-Wing Populism in the USA, UK and Australia’, Journal of Intercultural Studies 36, no. 5 (3 September 2015): 520–43.

12. John van Kooy, Liam Magee, and Shanthi Robertson, ‘“Boat People” and Discursive Bordering: Australian Parliamentary Discourses on Asylum Seekers, 1977-2013’, Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 37, no. 1 (18 April 2021): 13–26; Jennifer Merolla, S. Karthick Ramakrishnan, and Chris Haynes, ‘“Illegal,” “Undocumented,” or “Unauthorized”: Equivalency Frames, Issue Frames, and Public Opinion on Immigration’, Perspectives on Politics 11, no. 3 (September 2013): 789–807.

13. Andrew Markus, ‘Attitudes to Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Australia’, Journal of Sociology 50, no. 1 (1 March 2014): 10–22.

14. Glenn Stevens, ‘Economic Conditions and Prospects | Speeches’, Reserve Bank of Australia, 23 April 2010, https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2010/sp-gov-230410.html.

15. Tony McDonald and Steve Morling, ‘The Australian Economy and the Global Downturn Part 1: Reasons for Resilience’, The Treasury, 2 April 2012, https://treasury.gov.au/publication/economic-roundup-issue-2-2011/economic-roundup-issue-2-2011/the-australian-economy-and-the-global-downturn-part-1-reasons-for-resilience.

16. Nick Bryant, ‘Re-Thinking Big Australia’, BBC, 8 April 2010, https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/thereporters/nickbryant/2010/04/rethinking_big_australia.html.

17. IMF, ‘Australia’s Economic Outlook in Six Charts’, IMF, 21 February 2019, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/02/15/NA022119-australia-economic-outlook-in-six-charts.

18. Sarah Cameron and Ian McAllister, ‘Trends in Australian Political Opinion: Results from the Australian Election Study 1987–2019’ (School of Politics & International Relations, ANU College of Arts & Social Sciences, Australian National University, December 2019).

19. Ivar Krumpal, ‘Determinants of Social Desirability Bias in Sensitive Surveys: A Literature Review’, Quality & Quantity 47, no. 4 (1 June 2013): 2025–47.

20. James Dennison and Lenka Dražanová, ‘Public Attitudes to Migration: Rethinking How People Perceive Migration’ (Florence: Observatory of Public Attitudes to Migration, Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute, 2018).

21. Dennison and Dražanová, ‘Public Attitudes to Migration: Rethinking How People Perceive Migration’, 75.

22. Philipp Lutz and Marco Bitschnau, ‘Misperceptions about Immigration: Reviewing Their Nature, Motivations and Determinants’, British Journal of Political Science, 2 May 2022, 1–16.

23. Leong, ‘A Multilevel Research Framework for the Analyses of Attitudes toward Immigrants’.

24. John van Kooy, ‘Trust and Social Cohesion in Australia’, Social Cohesion Insights (Scanlon Foundation Research Institute, August 2022), https://scanloninstitute.org.au/sites/default/files/2022-08/Social%20Cohesion%20Insights_03_Aug22.pdf.

25. Bridget Judd, Peta Fuller, Tom Williams and Jessica Riga, ‘Budget 2022: Treasurer details budget in Press Club speech, after yearly inflation hits highest point since 1990 — as it happened’, ABC News, 26 October 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-10-26/live-updates-federal-budget-2022-reaction-jim-chalmers/101577442.

26. David De Coninck et al., ‘Linking Citizens’ Anti-Immigration Attitudes to Their Digital User Engagement and Voting Behavior’, Communications, 12 April 2022.

Back to top